One More Time: Stevenson’s “Across the Plains” and the Genre of Trans-American Travel

Caroline McCracken-Flesher

Published in Connotations Vol. 34 (2025)

Abstract

In 1879 Robert Louis Stevenson set out from Scotland and then travelled across America on the emigrant train. The narrative of his sea voyage troubled the sensibilities of his friends and father and was withdrawn from publication; the narrative of his transcontinental travels was published first in serial and then book form. This article considers Stevenson’s account of his American journey in the context of earlier and later emigration narratives. It pursues issues of space, place and progress, and of time as its perception shifts through experience. Stevenson’s journey activates not the “to” of historic travel or the “through” of the modern railroad; “Across the Plains” dwells, to the point of insistence, on the person traveling “in.” Given the complex publication history of Stevenson’s American travels, citations reference both the first publication of “Across the Plains” (as an article in two issues of Longman’s Magazine, 1883) and also Julia Reid’s The Amateur Emigrant, which brings together Stevenson’s sea and land voyages, and uses the manuscript for its copy text (Edinburgh UP, 2018).

Halfway through recounting his 1879 trip “Across the Plains,” Robert Louis Stevenson remembers how the train “shot hooting” down the canyons of the newly incorporated Wyoming Territory (Stevenson, [→ 190] “Across the Plains” 2.10: 373; ed. Reid 106). Stevenson pauses for a moment to express gratitude to the train, “as to some god who conducts us swiftly through these shades and by so many hidden perils” (“Across the Plains” 373, 374; ed. Reid 107). The perils are of the past: “Thirst, hunger, the sleight and ferocity of Indians are all no more feared,” he records, of a land now transected by the railway and compressed into rapid time and reachable space. “Yet we should not be forgetful of these hardships of the past,” he continues. Then “to keep the balance true,” he turns to “an original document,” retelling the story of a native attack upon a lone wagon “only twenty years ago” (“Across the Plains” 374; ed. Reid 107).

Stevenson’s reminiscence of his 1879 experiences first appeared in Longman’s Magazine over two issues in 1883. The conclusion of Part I had already emphasized what we should not forget: “one could not but reflect upon the weariness of those who passed by [Nebraska] in old days, at the foot’s pace of oxen” (2.9: 302; ed. Reid 102). Despite this insistence on remembrance, however, Stevenson’s narrative of his transcontinental journey may be most remarkable for its strategic forgetting. This paper locates the Stevenson who had cast off one continent for another within earlier and later discourses of westward travel, and thereby considers how his deliberately experiential writing and proto-naturalism perversely depend upon a spatial and literary emptiness that he himself laboriously constructs.

From the first, Stevenson’s westward voyage depended on the assertion of absence. Most obviously, Stevenson withheld news of his departure until it was practically accomplished, and he notified his parents (then in Scotland) only indirectly and by a delay, under enclosure to Sidney Colvin (who was then in England) (see Letters 3: 2). Moreover, Stevenson worked hard to remain outside parental access and knowledge, telling friends to write to him in Scotland via Charles Baxter (see Letters 3: 4). No one could reach him in San Francisco except by a doubled indirection, through the fiancé (unbeknownst to Stevenson, actually the husband) of his future daughter-in-law and, he insisted in addition, “under cover” (see Letters 3: 6n; 6-9). He even chased down his [→ 191] outgoing manuscripts in case he had carelessly entered an American return address that might circulate back to his parents and cause a family eruption (see 3: 8).

Within this energetically constructed emptiness, Stevenson would travel in space and time. He would race across an ocean and then a continent to Fanny Van de Grift Osborne, the married object of his affections, and change his life. As he traveled, he aimed, too, to expand in authorship. The sea voyage, because of its discomforts, he thought would make “the first part of a new book” (Letters 3: 5), and he recorded his experiences and impressions to that end (ed. Reid 7). Once in Monterey and properly at work, he reflected that the dual narrative of “The Amateur Emigrant” and “The Emigrant Train” should be “more popular than any of my others; the canvas is so much more popular and larger too” (Letters 3: 15). Indeed, the opening prospect of sea as well as continent constituted expectation and opportunity for more people than Stevenson. Critics waited eagerly, the Athenaeum’s “Literary Gossip” anticipating “a third set of his charming impressions de voyage” (7 February 1880: 185). “The book,” the Athenaeum declared with some certainty, “is called ‘The Amateur Emigrant,’ and sets forth how its author journeyed as a steerage passenger from Glasgow to New York, and how he afterwards went out West, from New York to California, in an emigrant train” (185-86).

The transatlantic voyage, however, together with its New York aftermath, turned out not so charming. It fell subject to criticism by Stevenson’s cadre of advisors and then to suppression because of parental prudishness about the unpleasantness of shipboard life (see Letters 3: 107n, 167). Thomas Stevenson, the author’s father, worried as well about negative reactions from the shipping line, with which he was in business (167n). Although the editor at Good Words, to which it had been submitted, thought it “capital—full of force and character and fine feeling, and quite the kind of thing which will suit” (Letters 3: 65n), Colvin, who acted as Stevenson’s main literary advisor, found it “bad” (76n). Thomas Stevenson told his son he considered it “altogether unworthy of you” (167n). Stevenson labored to please and to publish, and [→ 192] James D. Hart, in his restoration of Stevenson’s text, identifies deletions of up to about thirty percent to accommodate these criticisms before the proofs, still unacceptable, were bought up by Stevenson senior (see Hart xli-xlii). These deletions removed the “filth of men, women, and children living together in close quarters” that the first manuscript “pungently forced upon us” (xl). Stevenson himself gets a makeover: “A bit of fever and some general discomfort,” Hart writes, “Colvin could tolerate in print, but he could not allow a description of the vermin-infested body of Stevenson that had made him a mass of sores and reduced him to endless scratching” (xli; for Stevenson’s illness, see ed. Reid 82-83). On 23 October 1880, the Athenaeum “Literary Gossip” announced that “Mr. R. L. Stevenson has determined to suppress his ‘Amateur Emigrant’ […] and has withdrawn it from his publisher’s hands” (23 October 1880: 534). It was then that “The Emigrant Train,” still in development and ultimately published as “Across the Plains,” emerged as Stevenson’s alternate site of absence and as a stealthy manifestation of problematic presence. Stevenson’s transcontinental journey resists the landscape through which it travels and, his advisors’ disapproval notwithstanding, brings strongly to the fore the excess that is the author’s suffering body.

In the middle of the struggle over “The Amateur Emigrant,” Stevenson boosted this “second part” (Letters 3: 75). Though it was “written in a circle of hell unknown to Dante; that of the penniless and dying author,” he claimed of this travelogue—as he did of other texts—“I shall always think of it as my best work” (75). Yet he remembered with no great fondness “one page in Part 2 about having got to shore and rivers and sich [sic], which must have cost me altogether six hours of work as miserable as ever I went through,” and that he culled before publication in Longman’s. Bradford A. Booth and Ernest Mehew identify this as a passage restored in Hart’s edition (see Letters, 75n):

For we are creatures of the shore; and it is only on shore that our senses are supplied with a variety of matter, or that the heart can find her proper business. There is water enough for one by the coasts of any running stream; or if I must indeed look upon the ocean, let it be from along the seaboard, surf-bent, strewn with wreck and dotted at sundown with the clear lights that pilot [→ 193] home bound vessels. The revolution in my surroundings was certainly joyful and complete. (Hart 105-06; ed. Reid 88. Reid quotes MS as “me” not “one,” “surf-beat,” and “home-bound.”)

Making scenery yield to the passing body required its functional erasure. Hence the romantic passage just cited—and its later omission. Hence the execrable poetry that celebrated traveling “By flood and field and hill, by wood and meadow fair, / Beside the Susquehannah and along the Delaware” (Letters 3: 8) that Stevenson admitted in the moment “will rather stop a gap in the present than go down singing to posterity” (9), and that never made it beyond his letters. What remained of the Susquehanna River in Stevenson’s published text manifests a struggle for mastery over poetic allusions and tropes:

[It] was called the Susquehanna, the beauty of the name seemed to be part and parcel of the beauty of the land. As when Adam with divine fitness named the creatures, so this word Susquehanna was at once accepted by the fancy. That was the name, as no other could be, for that shining river and desirable valley. (“Across the Plains”2.9: 289; ed. Reid 88. Reid quotes MS as Susquehanna.)

Stevenson was laboring to clear the ground for his unique experience. That required the production and then the ruthless excision of both British and American literary traditions and affectations as he went.

Stevenson began his disengagement from established literary practice in the final chapter of his ship-board narrative—the text that his father suppressed. The transatlantic experience ends by putting the author ashore in New York, where he falls subject to the travails of a landward traveler. Poised to disembark, Stevenson recounts and mocks the well-known folktale of a benighted traveler in a den of thieves as a commonly held urban legend among the immigrant underclass about New York (see ed. Reid 73-74). He goes on to show the requisite architecture of hidden apertures echoed in his own lodging, and then to undermine the frisson by staying up all night not in fear of vagabonds but because of that “certain distressing malady which had been growing on me during the last few days” (80). When he goes to a pharmacy in search of relief, the chemist’s polite fiction that he must have a liver complaint [→ 194] only exacerbates his suffering and expands it upon the page: “I was ready to roll upon the floor in my paroxysms” (82). In the journey to come, story repeatedly would be usurped by suffering.

Riding the rails in “Across the Plains,” Stevenson worked his way through the narratives of America as imagined in contemporary Britain, and he similarly discarded them one by one. In Pittsburgh, he meets an African American waiter with such personal aplomb that the familiar codes supplied by Harriet Beecher Stowe in Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), or by shows of the blackface Christy Minstrels who toured Britain in the 1850s and 1860s (see Graham 28), cannot apply (see “Across the Plains” 2.9: 290; ed. Reid 89). “Imagine a gentleman,” he writes, “every inch a man of the world, and armed with manners so patronisingly superior that I am at a loss to name their parallel in England. […] familiar like an upper form boy to a fag; he unbends to you like Prince Hal with Poins and Falstaff” (“Across the Plains” 290; ed. Reid 89. Reid quotes MS: “fag,”). Ohio does not conform to the plots of the English Percy Bolingbroke St. John, whose Amy Moss Stevenson had read as a child and found disappointing, even then, for the “Indian brave, who, in the last chapter, very obligingly washed the paint off his face and became Sir Reginald Somebody-or-other” (291; Reid 90. Reid quotes MS: no commas after “who” and “chapter”). Stevenson’s memory was long: Amy Moss appeared in Cassell’s Illustrated Family Paper from May 13 to September 30, 1854. The plot roils with stolen children (three) and overt and apparent racism; “Custaloga” indeed performs as Stevenson remembers—and was rightly forgettable. Even the “six fat volumes” Stevenson carried with him (285; ed. Reid 84), the American George Bancroft’s History of the United States, prove to be only a burden, “ponderous tomes” to be hauled between stations in Chicago (293; ed. Reid 92).

If fictions populated the land east of the Missouri, the westward trail was heavily stocked with personal reminiscences that also stood as a challenge to an author who was constructing a strategic absence within which to assert his own story. John D. Unruh, Jr. notes that the overland emigrants from 1840 to1860 “took such pains to record their activities [→ 195] for posterity” that their writings constitute “a veritable ‘folk literature’” (Unruh 3-4). Adding to the information and experience that circulated as the shared discourse of emigration and settlement, many such narratives were widely accessible in print before Stevenson’s travels of 1879. Yi-Fu Tuan famously begins his Space and Place with a meditation on the Great Plains of America, what in the nineteenth century was loosely termed “the Great Desert” and—erroneously—considered uninhabited. “The Great Plains look spacious. Place is security, space is freedom: we are attached to the one and long for the other” (Tuan 3). And place for Tuan is effectively sedimented time; by repetition, by dwelling, place evolves from duration in space: “What begins as undifferentiated space becomes place as we get to know it better and endow it with value. […] place is pause; each pause in movement makes it possible for location to be transformed into a place” (6). As Stevenson traveled, he could not but be aware of earlier emigrant experiences that had translated wide open space into a place now recognizable to the white and European eye. Although his doggerel about the Delaware claimed “I have been changed from what I was before” (Letters 3: 8), the landscape around had been written into familiarity. After Nebraska’s “Desolate flat prairie” with only a yellow butterfly for distinction, the author registered “Bitter Creek […] a place infamous in the history of emigration” (Letters 3: 10-11). Stevenson presumably was drawing on emigrants’ shared knowledge, as expressed by A. K. McClure in 1869: “Bitter Creek […] is so impregnated with alkali that neither man nor beast can drink it without injury” (McClure 146). But such prior community consolidation of space into place left little room for the personal and literary expansion to be showcased through Stevenson’s travels.

How to make a mark? In Monterey, and waiting for his own romantic narrative to unfold, Stevenson recognized and thought to embrace the phenomenon of western sensation that was the dime novel. Alongside the account of his sea voyage, he drafted at least 85 pages of the “somewhat scandalous” novel, “A Chapter in the Experience of Arizona Breckonridge or A Vendetta in the West” (Letters 3: 26, 19). But as the first part of “The Amateur Emigrant” sank, the “Vendetta,” too, evaporated. What [→ 196] evolved in its place was a fast/slow retelling of the westward trail that translated a discourse often focused on the goals or the way points of travel into one centered on the traveler himself. For Bakhtin, “Time […] fuses together with space and flows in it (forming the road)” (Bakhtin 244), which then serves as a locus for encounter in which “the spatial and temporal series defining human fates and lives combine with one another in distinctive ways, even as they become more complex and more concrete by the collapse of social distances” (243). By contrast, Stevenson’s journey activates not the “to” of historic travel or the “through” of the modern railroad that now processed through knowable place, or even the “together” Bakhtin describes. Instead, “Across the Plains” dwells, to the point of insistence, on the person traveling “in.”

Stevenson’s longest disquisition on transcontinental travel falls in “The Desert of Wyoming.” Here the challenges of space and time, desire and experience align into thematic affect. In San Francisco, about five months after he had arrived on the west coast, Stevenson admitted his difficulty in writing “The Emigrant Train,” for he was “ill the whole time and [had recorded] scarce a note, only about three pages in pencil in a penny notebook” (Letters 3: 51). But it is precisely when he succumbs to illness on his journey that the literary contrast between travel and traveler comes into focus. The train progresses “Hour after hour” through an “unhomely and unkindly world” (“Across the Plains” 2.10: 372; ed. Reid 105). It seems “the one piece of life” amid a “paralysis of man and nature” (373; ed. Reid 106). Yet its progress seems infinitesimal only in this space and time: in fact, the train manifests the acceleration of a burgeoning commercial and industrial society, having been “pushed through this unwatered wilderness and haunt of savage tribes [to] bear an emigrant for some 12l. from the Atlantic to the Golden Gates” (373; ed. Reid 106. Reid quotes MS: “Emigrant” and “twelve pounds”). It is thus, Stevenson observes, “the one typical achievement of the age in which we live, as if it brought together into one plot all the ends of the world and all the degrees of social rank, and offered to some great writer the busiest, the most extended, and the most varied subject for an enduring literary work” (373; ed. Reid 106-07. Reid quotes MS [→ 197] “extended”—no comma). He concludes, however, “But alas! it is not these things that are necessary; it is only Homer” (384; ed. Reid 107). As for this writer, he did not attempt to emulate Homer or to anticipate Bakhtin. He focused elsewhere.

If Stevenson did not remember much of this segment of his travels because of his illness, it did not matter greatly, for it was his own experience, his own bodily affect, that stood central to “Across the Plains.” Writing to Colvin on the eve of his departure from Greenock, the author declared: “I have never been so detached from life; I feel as if I cared for nobody, and as for myself I cannot believe fully in my own existence I seem to have died last night; all I carry on from my past life is the blue pill” (Letters 3: 2-3). The pill was a remedy for diarrhea, and he joked to Baxter “it’s but little of my native land I’ll carry off with me” (3). In this moment the cynosure of every friendly and familial eye, this empty, suffering body, moving in space, would prove to be the amateur emigrant’s primary matter of personal and literary concern. Thus Stevenson arrives at his disquisition on the train, its slowness and speed, because of its expression through his body. “I had been suffering in my health a good deal all the way,” he tells us as he enters the “Black Hills of Wyoming,” and now that discomfort achieves prominence: “[The] evening we left Laramie, I fell sick outright” (“Across the Plains” 2.10: 372; ed. Reid 105). We then read a page and a half of powerful naturalist imagery focused on the suffering body: Stevenson, awake all night, describes his fellow travelers’

uneasy attitudes; here two chums alongside, flat upon their backs like dead folk; there a man sprawling on the floor, with his face upon his arm; there another half seated, with his head and shoulders on the bench. The most passive […] continually and roughly shaken by the movement of the train. […] the degradation of the air [is] intolerable […] Outside, in a glimmering night, I saw the black, amorphous hills shoot by unweariedly into our wake. (372-73; ed. Reid 106)

Day is no better.

It is this section that Stevenson concludes by a turn to history in the form of an 1860 letter held by his San Francisco landlady that told of [→ 198] her brothers’ journey and a native attack (“Across the Plains”2.10: 374-75; ed. Reid 107-08). (For the letter and its provenance, see ed. Reid fig. 2 and xxxv.) Yet if this narrative supplements Stevenson’s prose, adding past time and authentic memory, it also focuses attention on his use of external information when he misreads, overreads, or elaborates on the base narrative to imagine a scalping. Ryan et al. argue a perceptual difference between two kinds of travel narratives, one bearing the characteristics of a “tour,” the other deploying the capabilities of a “map” (Ryan et al. 8-9). The tour offers “a description of space from the point of view of a moving, embodied observer who visits locations in a temporal sequence” (Ryan et al. 8-9)—as one must when crossing a continent by train, and as does Stevenson. The map allows “a representation of space as seen from a fixed, elevated point of view that affords the observer a totalizing, simultaneous perception of the relations between objects” (9)—as in Stevenson’s remembered travel which can, if it would, draw on narrative assumptions and literary tropes. In this instance, it does. A. K. McClure undertook the westward journey as a “tour” just as “the great overland route” (McClure 18) was becoming pacified, and two years before the railroad would substantially alter the landscape and dynamic of travel. “Still,” he insists, “it is exposed to perils not known in the boundaries of civilization” (18). He goes on to fill his sensational and racist account with second-hand stories of scalping of the innocent pioneer (see 100-01, 108, 131, 252, 311, 355-57). Sarah Raymond Herndon, who traveled in 1865 and then serialized her account in the Rocky Mountain Husbandman beginning May 1880—while Stevenson was still working on his remembrances—more reliably cites specific cases. Of July 16, 1865, she recounts an event that took place one week before her wagon train passed Rock Creek: two men who had fallen behind a previous group were found “dead, and scalped,” their wagons set on fire (Rocky Mountain Husbandman 9 September 1880: 5). Stevenson, it seems, performs the “tour”; at the same time, he adopts a particular perspective, highlighting parts of the “map” that may be actual (as in Herndon), but that are also becoming literary (as in [→ 199] McClure). If conventional tales of travel, such as the scary stories Stevenson heard in New York or St. John’s overwrought imitations of James Fenimore Cooper, proved easy to recognize and elude, it was no small task to resist a burgeoning western narrative.

Largely, however, Stevenson succeeds, mapping for his audience that much less familiar territory: himself. Four narratives published before and alongside Stevenson’s travels help make the case. Three recount Gold Rush-era travel to California: Martha M. Morgan’s A Trip Across the Plains in the Year 1849 (published in 1864), James Abbey’s A Trip Across the Plains, in the Spring of 1850 (published in 1850), and physician George Keller’s A Trip Across the Plains, and Life in California (recounting an 1850 trip and published in 1851). Herndon’s 1880 serialization, “Crossing the Plains in 1865,” follows the westward trail to the Montana cut-off. These show how much Stevenson’s narrative pursued well-trodden ground, inscribed by its own accumulation of literary tropes, but also how he departed from it. Theirs is not the tale Stevenson tells.

In some respects, despite its originality for the British audience, Stevenson’s tale broke no new ground. For instance, however many rivers and canyons, mountains and even volcanoes stood between the Missouri and the Pacific Ocean, the imaginative life of America had already and definitively launched itself “across the plains.” Numerous works published before Stevenson’s travelogue used the exact phrase as a title or subtitle. In addition to the four listed above, there are also at least Ingalls (1852), Udell (1859), and Ludlow (1870) in book form, and many in newspapers. “Crossing the Plains” also surged as term and as trope, in a range of prints of which George Holbrook Baker’s 1853 series in “Hutchings Panoramic Scenes,” may be best known. The phenomenon became generic to the degree that the Century Magazine in 1902, in an article illustrated by Frederic Remington, looked back and joked that “In the rude ballads and songs of [the 1850s], the phrase for crossing the plains was ‘the plains across’; never by any chance did the verse-maker write ‘across the plains.’ […] to this day you will find old pioneers […] who never admit that they came across the plains; they came [→ 200] the plains across” (Brooks 803). To cross the plains—as a trend, as a tale and as a title—by Stevenson’s time of writing was firmly fixed in the American imaginary.

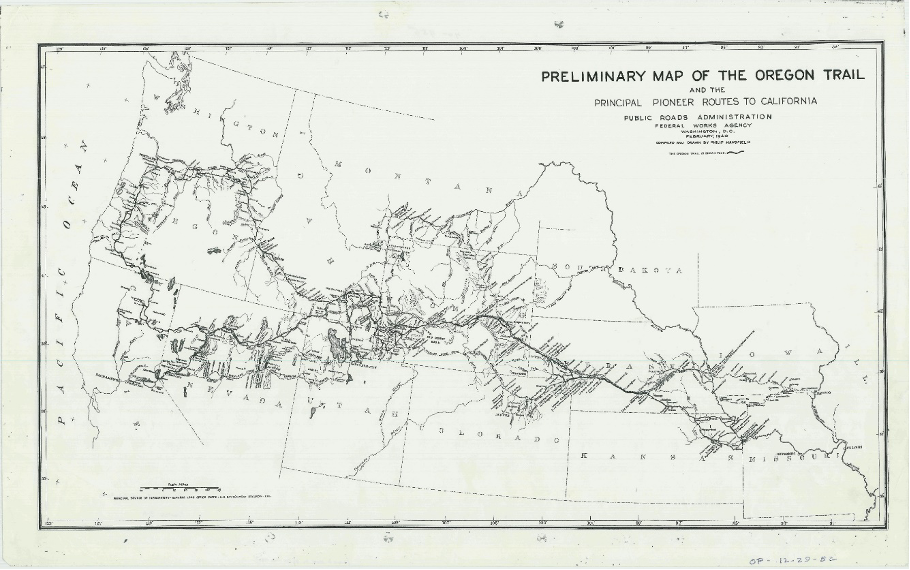

Fig. 1: A map of the nineteenth-century emigrant trails across America, National Archive RG30OregonTrail.

Of the plains themselves there was agreement, too: Sarah Herndon, like Stevenson, laments the “tedious, tiresome, monotonous view of these vast prairies” (Herndon, entry for 10 May 1865, “Crossing the Plains in 1865,” Rocky Mountain Husbandman 10 June 1880: 5). Like Stevenson, many travelers express astonishment at the sheer numbers heading west and also returning east. Unruh calculates that as early as 1841, “nearly 10 percent of the departing caravan […] made their way back to the Missouri settlements” from which they had launched their travels (Unruh 122). The traffic was never one way, no matter how much that surprised Stevenson as he passed through this well-traveled space for the first time.

In contrast to Stevenson, however, these laborious journeys, often walking alongside the ox-drawn wagon, dwell on practicalities, rehearsing distances and feeding grounds for cattle, cut-offs to speed the [→ 201] way, the perils of overloading, and the strategies to ford streams or winch teams down precipitous slopes. Charles W. Baley observes of Udell’s journals that, “typical of many emigrant journals of the period […] He recorded mostly such things as weather and road conditions, locations of campsites, availability of water, grass, and firewood, number of miles traveled each day, and the distance of each camp site from the Missouri River” (Baley 180-81).

More notably, these narratives manifest a frontier constantly shifting under pressure of immigration, and a relativity to time produced by differing modes of transportation and delivery. Sarah Herndon, on her trusty pony, on 19 June 1865 overtakes an old friend who is night herder for a slow-traveling wagon train of freight (Herndon, Rocky Mountain Husbandman 29 July 1880: 5). All around, fast and slow, go the walkers, the wagons, the wagon trains, the processions of freight wagons (see Unruh 106-107, 10). Messages stand still, pinned to a post (Unruh 131-33), languish or leap ahead by mail (Hewitt 110-14, 209-10, 462; Collins Part I: 22), and after 1861 might even hum by on the telegraph line (see McClure 28).

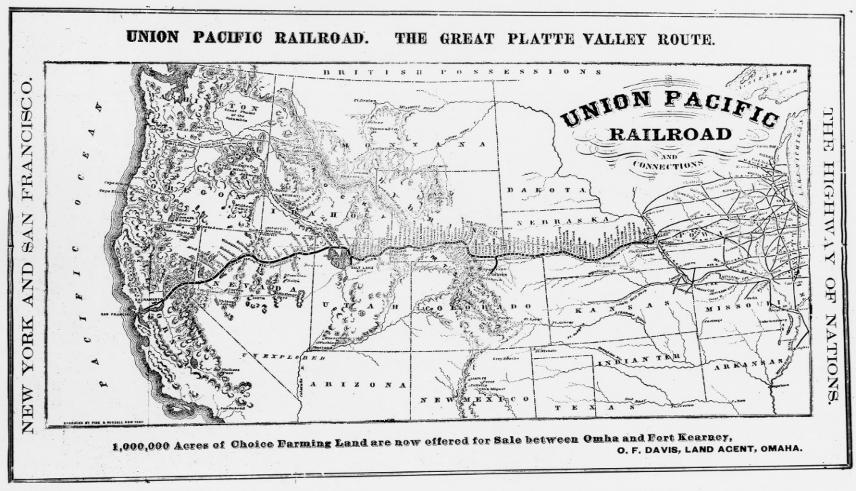

For Stevenson in 1879, following the relatively direct route of the transcontinental railroad, now ten years old, the experience inevitably differed.

Fig. 2: An 1870 map of the Transcontinental Railway line, which had been completed in 1869. American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming.

[→ 202] Trains did stop frequently to take on wood and water, and Stevenson describes delays along with the inconvenience of changing stations in Chicago. By the standards of the day, however, he did, as he said, proceed “swiftly” and “skim these horrible lands; as the gull, who wings safely through the hurricane and past the shark” (“Across the Plains” 2.10: 374; ed. Reid 107).

Was it the speed of his transit or his focus on California, his journey “through” and “to,” that made the middle of America for him a vast vacancy? Travelling at speed, to Stevenson his progress felt slow; eager to record, he yet ignored the accumulated prairie trash of abandoned objects with which two generations of immigrant wagons had marked their way through the landscape (see Unruh 150). He commented to no extent on the giant western trains with their spark and cattle catchers, unlike Isabella L. Bird who in 1873 bounded off the train to explore the scenery at every opportunity, and then appreciated the “huge Pacific train, with its heavy bell, thunder[ing] up to the door” of her Truckee lodging house (Bird 25). Stevenson muted the memory of a Civil War scattered along the line in the multiplied towns called Sherman, the native culture suppressed on behalf of the union by Confederate prisoners of war (see Herndon, 10 June 1865, Rocky Mountain Husbandman 15 July 1880: 5), or the tattered uniforms that now clothed the west. Where he noticed the demoralized natives “dressed out with the sweepings of civilisation,” dwelt on the “truly cockney baseness” of his fellow passengers, and made an impassioned plea for justice (“Across the Plains” 2.10: 381; ed. Reid 115), Bird focused on the natives themselves in an extensive (if tacitly racist) anthropological report (Bird 4-5). Stevenson provided no such detail.

Stevenson had been working on detachment, beginning by detaching himself from Scotland. If he left his parents without a word, the idea of separation was not new and ran deep. In Edinburgh: Picturesque Notes, published the same year as he leaped across the Atlantic, Stevenson invoked those who “aspire angrily” (Edinburgh: Picturesque Notes 3) to escape Edinburgh’s bounds. With a thinly disguised autobiographical impulse, he described how, leaning over “the great bridge which joins [→ 203] the New Town with the Old” and that spans Edinburgh’s Waverley Station, they might “watch the trains smoking out from under them and vanishing into the tunnel on a voyage to brighter skies.” Such “[h]appy […] passengers” could “shake off the dust of Edinburgh” and head to “that Somewhere-else of the imagination.” Having finally caught that train to the “Somewhere-else of the imagination,” the space of Stevenson’s imagination proved fully occupied not by the experiences of the travelers who preceded him, or much by those who lived along the line, but by his own travails. In Ryan’s terms, for Stevenson the American landscape served largely as “the environment in which narrative is physically deployed […] the medium in which narrative is realized” (Ryan 1). This narrative was all about Stevenson.

The displacement of Stevenson’s narrative into America and away from British people and sensibilities was enough to satisfy Sidney Colvin. Reading it on an English train, the critic found himself “chortling at frequent intervals,” and apparently missing the depravities of “The Amateur Emigrant” that had so concerned him (Letters 3: 76). But al-though Stevenson may have taken a sidestep into American spaces and into the no-place that was a transcontinental train on the move, away from Edinburgh and its norms his “late-Victorian degenerationist rhetoric” (Reid, Bottle Imp) in fact becomes considerably exaggerated. In the face of much modernity, it is animal images that abound. Worse, where earlier travelers noted the bison and antelope, shot the unfortunate snakes and played among the prairie dogs, Stevenson narrowed his gaze from the space extending all around him to the crowd of human animals inhabiting the “American railroad-car, that long, narrow wooden box, like a flat-roofed Noah’s ark” (“Across the Plains” 2.9: 296; ed. Reid 95. Reid quotes no hyphens). Having passed the desert of Wyoming, and constricted our vision to the night-time sleepers, sagging in body, “continually and roughly shaken by the movement of the train” (2.10: 373; ed. Reid 106) and making animal murmurs in their sleep, the one waking/suffering sensibility turns his attention to the stink of train cars continually occupied for ninety hours. The air is “rancid,” “pure menagerie, only a little sourer, as from men instead of monkeys” (376; [→ 204] ed. Reid 109. Reid quotes “menagerie;”). He explicitly aligns humans with apes and the Yahoos of Gulliver’s Travels and acknowledges—and resists—the pressure to become “such another as Dean Swift; a kind of leering, human goat, leaping and wagging your scut on mountains of offence” (376; ed. Reid 109. Reid quotes MS: “Swift:” “leering” “scut,” “offense”). In Stevenson’s progress, we are thoroughly immersed in travel—the travail seeping through every sense and centered, for readers sitting uncomfortably at home, in our author’s own body. The yahoos on board take Stevenson, in his illness, for their mark (377; ed. Reid 110-11), but he has already untethered his text and travels from literary and cultural expectation. The author extended a vacancy of perception all around that leaves as the cynosure for every eye his own visibly suffering body—with which no respectable American wishes to “chum” (2.9: 296-97; ed. Reid 95-96) or double up at night on the train.

Later writers crossing the plains begin to echo Stevenson’s discourse. Indeed, between Sarah Herndon’s 1880 reminiscence of her 1865 travels and their book publication in 1902, she takes up Stevenson’s powerful imagination of how “at each stage of the [railroad’s] construction, roaring, impromptu cities, full of gold and lust and death, sprang up and then died away again, and are now but wayside stations in the desert” (2.10: 373; ed. Reid 106. Reid quotes MS “sprang up,”). Looking back at her travels by pony and ox-drawn wagon, she adds a paean to “this town of tents and wagons [that] has sprung up since yesterday morning when there was no sign of life on this north bank of the South Platte, and now there are more than one thousand men, women and children, and I cannot guess how many wagons and tents” (Herndon, Days on the Road 123). Herndon seems to have adapted Stevenson’s observation of the railroad’s industrial-strength capitalism to the walking pace of the ox and the haulage capacity of the cart. G. W. Thissell, remembering his 1849 travels from the vantage of 1903, falters at what “No pen can describe” (Thissell 10)—a cholera epidemic—before he has even disembarked at St. Louis on his way west. Delayed ashore, Thissell himself is ill, but unlike in Stevenson, the suffering is generalized, as “many sickened and died [and others] sold their out-fits and returned home” [→ 205] (Thissell 11). Illness has moved center stage; its specificity, however, has not.

Stevenson’s influence, if any, proved fleeting in the discourse of late-century westward narratives. Remembering his launch across “the border line of civilization” that was Council Bluffs, a mere way-station for Stevenson, Thissell begins populating the landscape both with rural stores and settlements that Stevenson overlooked, and with stories bearing strong resemblance to the tall tale: “thrilling adventures and hair-breadth escapes from death, as well as many amusing incidents” (7). Then, by 1907, speed and sensation overtake any hope of Steven-sonian sensibility when Clarence Young’s “Motor Boys” head “Across the Plains” in their “big touring car” (Young, Motor Boys [1907] Preface).

What, then, did Stevenson achieve through his voyage across the plains? Thinking again about “The Amateur Emigrant,” and with “Across the Plains” still in production, Stevenson realized that “I could also leave out the names of the Clyde and the like; so that it could be identified with nowhere” (Letters 3: 167). And in the end, whereas later authors drew on the author’s slim volume as one more intertext, Stevenson’s unique contribution to the westward narrative is forgetfulness. Such a deliberate forgetting of literature and of landscape centers the gaze on the suffering space that was the traveling author. This was a territory both attractive and uncomfortable to inhabit—a compelling territory for realist and naturalist authorship. It is a territory that would wait to be fully unfolded until James Joyce, in Ulysses, sent Leopold Bloom’s unwieldy body on its progress around a Dublin both overfull and, one might argue, ultimately irrelevant.

Works Cited

Abbey, James. A Trip Across the Plains, in the Spring of 1850, Being a Daily Record of Incidents of the Trip over the Plains, the Desert, and the Mountains, Sketches of the Country, Distances from Camp to Camp, etc. And Containing Valuable Information to Emigrants as to where they will find Wood, Water, and Grass at almost every Step of the Journey. New Albany, IN: Kent and Norman, and J. R. Nunemacher, 1850.

Baker, George Holbrook. “Crossing The Plains.” Illus. from “Hutchings Panoramic Scenes.” Placerville: Sun Print, 1853.

Bakhtin, Mikhail M. “Forms of Time and of the Chronotope in the Novel.” The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Ed. Michael Holquist. Austin: U of Texas P, 1981. 84-258.

Baley, Charles W. Disaster at the Colorado: Beale’s Wagon Road and the First Emigrant Party. Logan, UT: Utah State UP, 2002.

Bird, Isabella L. A Lady’s Life in the Rocky Mountains. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1879-80.

Brooks, Noah. “The Plains Across.” Century Magazine 63.6 (April 1902): 803-20.

Collins, John S. Across the Plains in ’64. Omaha: National Printing Company, 1904.

Graham, Eric. “The Black Minstrelsy in Scotland.” Scottish Local History 80 (February 2011): 21-30.

Hart, F. R. Robert Louis Stevenson: From Scotland to Silverado. Cambridge, MA: Belknap P, 1966.

Herndon, Sarah Raymond. “Crossing the Plains in 1865.” Rocky Mountain Husbandman. (27 May-2 Dec 1880).

Herndon, Sarah Raymond. Days on the Road. Crossing the Plains in 1865. New York: Burr, 1902.

Hewitt, Randall H. Over the Divide: A Mule Train Journey from East to West in 1862, and Incidents Connected Therewith. New York: Broadway, 1906.

Ingalls, E. S. Journal of a Trip to California by the Overland Route Across the Plains in 1850-51. Waukegan: Tobey and Co., 1852.

Keller, George. A Trip Across the Plains, and Life in California; embracing a description of the Overland Route, its Natural Curiosities, Rivers, Lakes, Springs, Mountains, Indian Tribes, &c. &c.; The Gold Mines of California: Its Climate, Soil, Productions, Animals, &c., with Sketches of Indian, Mexican and Californian Character: to which is added, A Guide of the Route from the Missouri River to the Pacific Ocean. Massillon: White’s P, 1851.

“Literary Gossip.” Athenaeum 2728 (7 Feb. 1880): 185-87.

“Literary Gossip.” Athenaeum 2765 (23 Oct. 1880): 534.

Ludlow, Fitz Hugh. The Heart of the Continent: A Record of Travel Across the Plains and in Oregon, with an Examination of the Mormon Principle. New York: Hurd and Houghton, 1870.

McClure, A. K. Three Thousand Miles through the Rocky Mountains. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1869.

Morgan, Mrs. Martha M. A Trip Across the Plains in the Year 1849, with Notes of a Voyage to California, by Way of Panama. Also some Spiritual Songs, &c. San Francisco: Pioneer P, 1864.

Reid, Julia. “‘[N]ewspaper like in style, and not worthy of R. L. S.’: Robert Louis Stevenson’s ‘The Amateur Emigrant.’” Bottle Imp 12 (November 2012). https://www.thebottleimp.org.uk/2012/11/newspaper-like-in-style-and-not-worthy-of-r-l-s-robert-louis-stevensons-the-amateur-emigrant/

Ryan, Marie-Laure, Kenneth Foote and Maoz Azaryahu. Narrating Space/Spatializing Narrative: Where Narrative Theory and Geography Meet. Columbus: Ohio State UP, 2016.

Stevenson, Robert Louis. “Across the Plains.” Longman’s Magazine 2.9 (July 1883): 285-304; 2.10. (Aug. 1883): 372-86.

Stevenson, Robert Louis. “The Amateur Emigrant.” Robert Louis Stevenson: From Scotland to Silverado. Ed. F. R. Hart. Cambridge, MA: Belknap P, 1966. 1-99.

Stevenson, Robert Louis. Edinburgh: Picturesque Notes. London: Seeley, Jackson, and Halliday, 1879.

Stevenson, Robert Louis. The Amateur Emigrant: With Some First Impressions of America. Ed. Julia Reid. The New Edinburgh Edition. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2018.

Stevenson, Robert Louis. The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson. 8 vols. Ed. Bradford A. Booth and Ernest Mehew. New Haven: Yale UP, 1994-95.

St. John, Percy Bolingbroke. Amy Moss; or the Banks of the Ohio: A Tale of Domestic Adventure. Cassell’s Illustrated Family Paper 20-42 (13 May-30 September 1854). Repr. London: Cassell, Petter, and Galpin, 1860.

Thissell, G. W. Crossing the Plains in ’49. Oakland: n.p., 1903.

Tuan, Yi-Fu. Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1977.

Udell, John. Incidents of Travel to California Across the Great Plains. Jefferson, OH: Ashtabula Sentinel Steam P, 1856.

Udell, John. Journal of John Udell, Kept During a Trip Across the Plains, Containing an Account of the Massacre of a Portion of his Party by the Mojave Indians in 1859. Solano County Herald 1859. Jefferson OH: Ashtabula Sentinel Steam P, 1868.

Unruh, John D., Jr. The Plains Across: The Overland Emigrants and the Trans-Mississippi West, 1840-1860. Urbana: U of Illinois P, 1993.

Young, Clarence. The Motor Boys Across the Plains. New York: Cupples & Leon, 1907.

Young, Clarence. The Motor Boys Overland or A Long Trip for Fun and Fortune. New York: Cupples & Leon, 1908.