From Illustration to Meme: The Pictorial Representation of Duality in Editions of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

Wolfgang G. Müller

Published in Connotations Vol. 34 (2025)

Abstract

This essay investigates illustrations of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886), spanning the time from the pictorial representations of the beginning of the twentieth century to the memes of the digital age. As the title of the tale suggests, its focus is on two figures who turn out to be actually manifestations of one person. The orientation on a pair of two closely interrelated figures is rendered in the illustrations in increasingly inventive ways, while the text retains its incomparable art of suggestion and implication. The main object of the article is to explore the ways illustrators have risen to the challenge of representing duality. Extensive attention is given to Macauley’s illustrations (1904), which are quite close to the text, capturing the atmosphere of the city, describing the main figures and their actions as well as presenting moments and motifs which reflect the phenomenon of duality. Important graphical and aesthetic innovations are verified in S. G. Hulme Beaman’s illustrations (1930). Hulme Beaman’s cover illustration is interpreted as heralding, in the representation of the names of Jekyll and Hyde together with the pictorial representation, the arrival of the meme as a unit of cultural discourse. The memes of Jekyll and Hyde have, in their wide distribution over the world, become an important element of popular culture.

[→ 248] Introduction

Among the multitude of possible relationships between different literary works, the re-use or variation of pre-existent figures (characters) plays an important part, a phenomenon which has been called interfigurality (Müller, “Interfigurality”). A specific re-use of literary figures, which is relevant in the context of the present paper, is the transfer of the figure(s) into visual media such as plays, films, musicals, paintings and book illustrations (Müller, “Literary Figure into Pictorial Image”). This transfer presents a particular artistic challenge if the identity of the figures is fluid, as is the case in Stevenson’s narrative: the title of the text suggests two protagonists, identified by name on the cover or frontispiece of the book, which assigns to them separate civic identities (Dr., Mr.). In the course of the narrative these personages prove to be actually one figure or, more precisely, two insolubly connected variants or versions of one and the same person.

This paper attempts to show how illustrators have made efforts to give graphic clues to the dualistic nature of the pair of Jekyll and Hyde. However, we have to be aware that illustrations of a novel do not and cannot simply provide pictorial equivalents of narrative givens, since the two media have their own aesthetic principles as much as modes of expression and production. The titular figures of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde are from first to last characterized by such a pervasive interconnectedness and ambiguity in their narrative presentation that an analogous graphic representation of their duality can hardly reach the complexity and sophistication of the original written text. More specifically, we have to be aware of the fact that Stevenson’s tale presents a sequence of different perspectives. We perceive the action and the involved characters through the eyes of varying figures who are differentiated by the author in a masterly manner. This technique can hardly be responded to in illustrations. Yet illustrators have produced miraculous results in their attempts to represent Jekyll and Hyde and their shared identity, even if—or because—they deviate from the original at times. An important aspect of the reception of the pair of Jekyll and Hyde is the fact that in the digital age the meme as “a unit of cultural transmission, or a [→ 249] unit of imitation” (Dawkins) becomes a a key instrument for the dissemination of this configuration. It is by the meme that Jekyll and Hyde gained unparalleled presence in popular culture. And the meme equally turns out to be a catalyst even in deluxe illustrated editions of Stevenson’s work.1

Charles Raymond Macauley’s Edition (1904) as an Early Illustrated

Jekyll and Hyde

Before we deal with individual illustrations of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, a brief word on terminology and a general comment on illustrated versions of Stevenson’s novel is necessary. It has to be stressed that Stevenson never designed his text as an illustrated narrative. That is why the term “iconotext,” used by Peter Wagner and others for narrative works that, like Dickens’s novels, combine both verbal and visual representation, is inadequate for the text under discussion. Standard editions confine themselves to the text and do without illustrations, except for the occasional use of cover images (and a few other instances like the one in fig. 1). Yet Stevenson’s text has so much descriptive strength and evocative power that a transformation into a graphic mode of representation comes as no surprise.

The first edition of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde appeared in 1886; the first illustrated edition, crafted by Charles Raymond Macauley, was published in 1904. Later editions, especially those designed for teaching purposes, for instance Usborne English Readers Level 3 (illus. Valdrigi, 2021), and comics, for instance Classics Illustrated (illus. Cameron, 2016), offer illustrations with a marked tendency to reduce the textual component while enhancing the visual dimension. The process of a popularization of a literary work with an avid reception by other media and genres such as theatre, musical, film and comic can here be observed in an exemplary way. The focus of the following investigation will be mainly on the rendition of the relation between Jekyll and Hyde. It will be asked if, and if so, in which ways the two media brought together in this case interact cognitively and aesthetically, and if there is [→ 250] something like a semantic and aesthetic surplus to be noticed in this amalgamation.

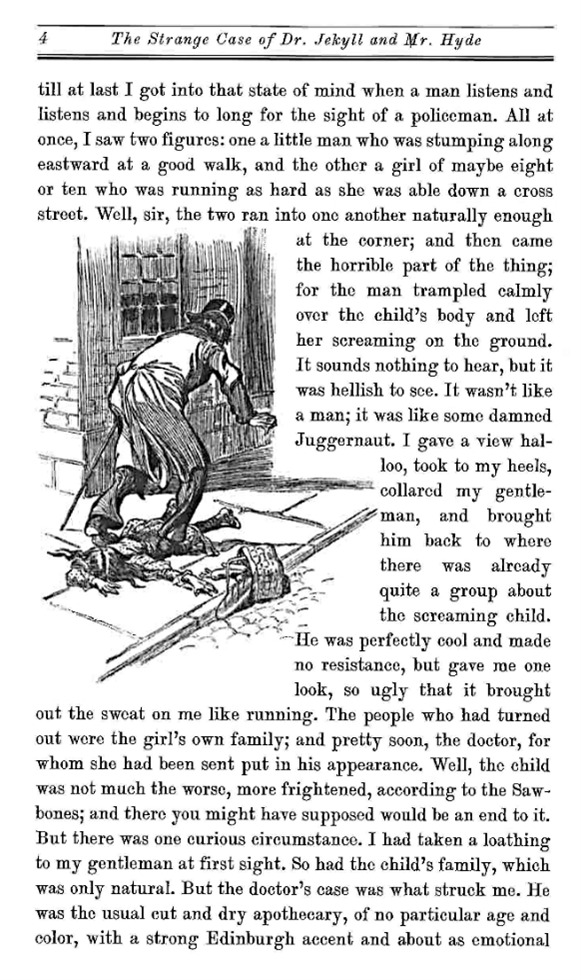

Fig. 1: “Story of the Door” by Charles Raymond Macauley (1904). Rpt. in The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde. Orinda, CA: SeaWolf P, 2023.

The first illustration from Macauley’s edition to be commented on, actually one of the smallest illustrations in the edition, is Mr. Hyde’s act of callous indifference against the little girl close to the door of his habitation (fig. 1). Though the illustration, which is integrated into the narrative text, may seem sketchy, it is rewarding to have a closer look. It does not and cannot represent the action in its temporal progression, but it singles out a moment which it arrests in such a way that the reader/spectator can sense and quasi co-experience the forward motion of the “Juggernaut,” as he is called (Tusitala Edition 3). The opposition of aggressor and helpless victim is expressed by the contrast of size and position of the abuser and the girl, who is trampled over and is now lying stretched out helplessly on the pavement. An aspect to be noted is Hyde’s body height. He is repeatedly referred to as a small [→ 251] man, the opposite of a stately person. The illustration appears to strongly contrast with Hyde’s small body height as noted in the text. Incidentally, in “Henry Jekyll’s Full Statement of the Case” Dr. Jekyll provides a plausible explanation for the fact “that Edward Hyde was so much smaller, slighter, and younger than Henry Jekyll” (Tusitala Edition 60-61).

Another significant aspect is that Stevenson makes Enfield, a man-about-town, recount the scene to the lawyer Utterson. Enfield is a rather straightforward man. He feels outraged by what has happened and compares Hyde to Satan, but he retains a certain coolness, and his report is brisk and vivid. He says that Hyde is disgusting-looking but finds himself stumped when asked to describe the man. When he compares the abuser to a “Juggernaut,” he characterizes his machinelike action of trampling over the little girl, which is well expressed by the illustration. In this respect, the illustration provides an equivalent of the text. Perhaps it can even be regarded as a sign of withholding extreme emotionality that just this illustration is so small.

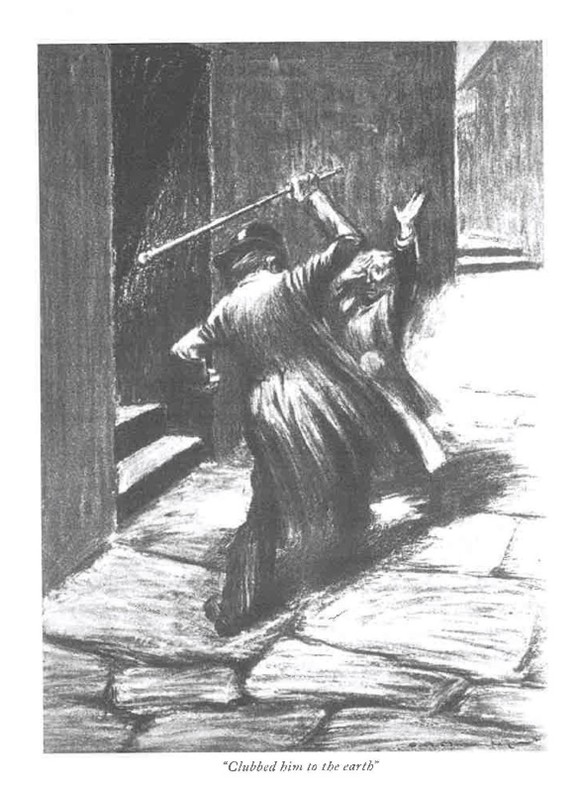

Fig. 2: “The Carew Murder Case” by Charles Raymond Macauley (1904). Rpt. in The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde. Orinda, CA: SeaWolf P, 2023.

[→ 252] The next picture represents the murder of a well-esteemed gentleman, MP Sir Danvers Carew, which in the narrative is described from the perspective of a maid servant in the upper floor of a neighbouring house (fig. 2). The point of reference is the statement “clubbed him to the earth” (Tusitala Edition 21). In the text, the serene mood of a peaceful night is interrupted by the brutality of a motiveless murder, a change which the illustration focusing on a moment in time cannot represent. Carew, a man who had accosted Hyde most kindly in the street, is attacked by him in a fury of anger. Again, a moment is singled out by the illustration, the aggressor brandishing his cane, the victim helplessly raising an arm and shielding his eye with his other hand. The horror of the action is here represented more intensively than in the first scene of violence. Stevenson now musters up his capacity for arousing the reader’s emotions. We must always be aware of changing viewpoints and special narrative effects and ambiguities of the story. In this case the terrible event is shown from the perspective of the maid. As impressive as the illustration may be, it cannot convey the full horror of the scene, with the maid watching the murderer “trampling his victim under foot, and hailing down a storm of blows,” while the horrified maid loses consciousness. To represent such a scene visually in its full temporal extension, the medium of film would be a visually and acoustically more adequate, though Macauley’s achievement is admirable. It is interesting that there is a similarity of perspective in the representation of the two brutal acts by Hyde. There are similar points of view, a similar difference in body height between Hyde and his victim, similar actions (the act of trampling) and, most importantly, the abuser is shown from the back, probably to avoid showing his face. [→ 253]

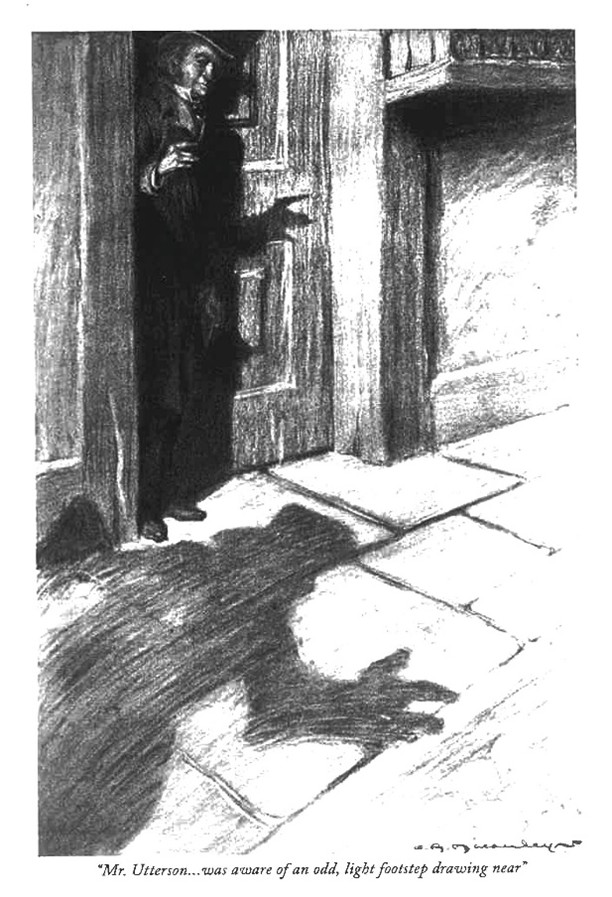

Fig. 3: “Search for Mr. Hyde” by Charles Raymond Macauley (1904). Rpt. in The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde. Orinda, CA: SeaWolf P, 2023.

The next illustration (fig. 3), once more gives evidence of the artist’s reluctance to confront us directly with Hyde, now in the scene of Utterson’s search for Hyde and his encounter with the mysterious personage. Stevenson turns this confrontation of a representative of the solid middleclass lawyer and a mysterious suspicious outsider into one of the great moments of mystery fiction. Utterson accosts Hyde and actually asks him to show his face. Hyde complies with this demand after some hesitation. The illustration here deviates markedly from Stevenson’s text. It restricts itself to the shadow of Hyde, and, what is more, it shows just the shadow of the back of the person, thus emphasizing the mysteriousness and indeterminacy of the apparition. Macauley’s supreme art of illustration is additionally indicated by the fact that, when Utterson is waiting for Hyde, both throw a similar shadow of their hand. It is significant that the frontispiece of Macauley’s edition has an image of Hyde in a position like the picture of him trampling over the girl (fig. 1), but instead of the victim there is just the abuser’s black [→ 254] shadow to be seen underneath him. That the shadow of a person is related to his or her identity is a commonplace in nineteenth-century literature. A well-known example is Adalbert von Chamisso’s story Peter Schlemihl (1814).

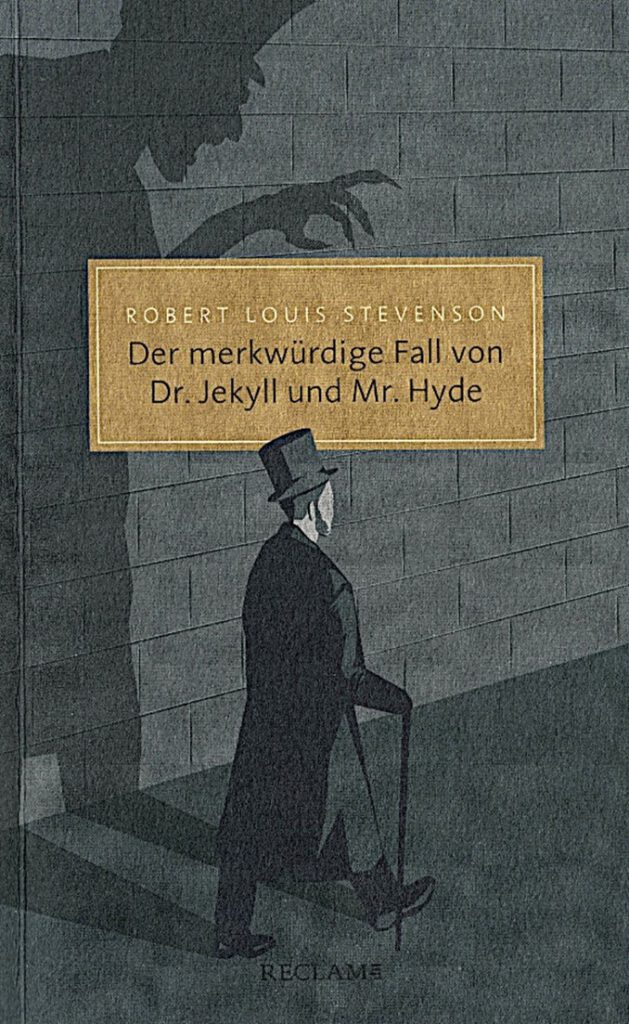

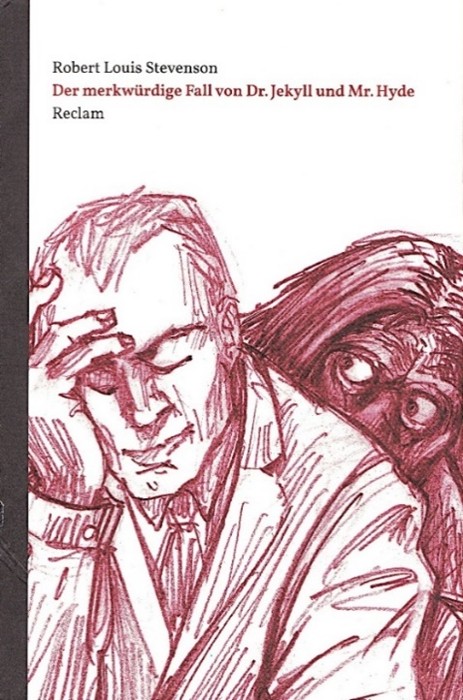

Fig. 4: Der merkwürdige Fall von Dr. Jekyll und Mr. Hyde. Ditzingen: Reclam, 2020.

A German Reclam edition of 2020 has an impressive cover illustration of Jekyll (fig. 4), dressed elegantly with a top hat and a walking stick, and the shadow of Hyde looming over him with a ghastly, contorted face, actually on the point of his hand of grasping him. Alternatively, Hyde could be holding a puppet-like Jekyll on string (an interpretation I owe to Isabel Vila Cabanes). [→ 255]

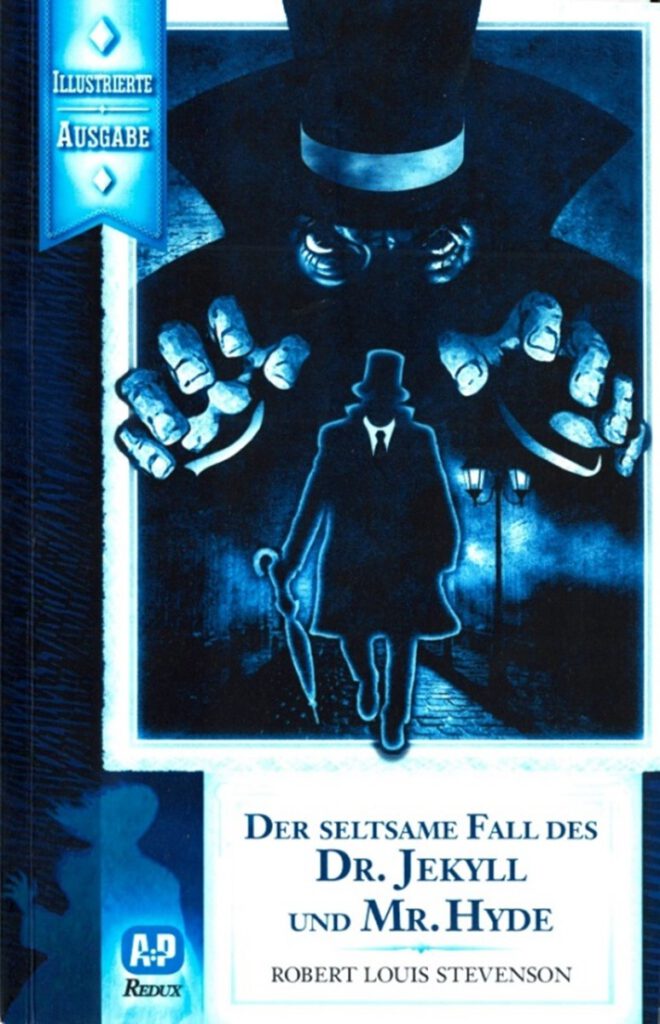

Fig. 5: Der seltsame Fall des Dr. Jekyll und Mr. Hyde. German Edition. Illus. Tracy Tomkowiak. N.p.: Alden P, 2023.

An interesting use of this motif (fig. 5) is to be found in the cover of a German edition of 2023. The shadow of Hyde assumes a threatening power, seeming to hold the body of Jekyll in its clutch, with the latter’s size diminished radically. Stevenson’s opposition of a tall Jekyll and a small Hyde is here inverted. On the whole this illustration is a good example of interfigurality in the context of duality. What can be noticed is the attempt to outdo earlier treatments of this particular motif, a phenomenon which will be dealt with in the context of the meme theory. [→ 256]

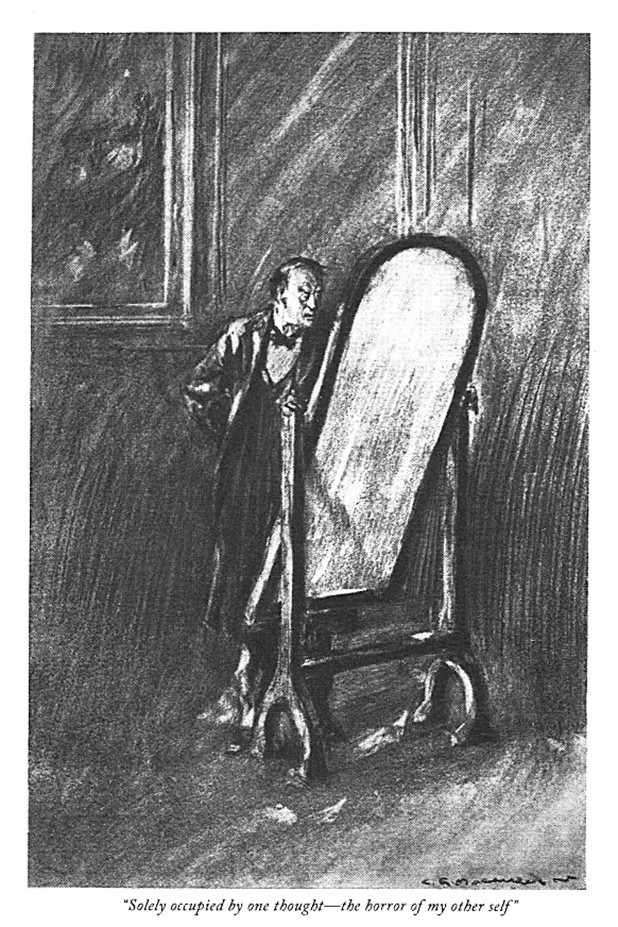

Fig. 6: “Henry Jekyll’s Full Statement of the Case” by Charles Raymond Macauley (1904). Rpt. in The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde. Orinda, CA: SeaWolf P, 2023.

Another image (fig. 6), which Macauley uses in order to signify the problem of identity, is that of the mirror. In Stevenson’s tale this image appears only in the last chapter, “Henry Jekyll’s Full Statement of the Case,” where the mirror is of paramount importance. Originally Jekyll had no mirror in his room. It was brought there “for the very purpose of those transformations” (Tusitala Edition 60). Jekyll uses it to perceive changes of his physical appearance, being increasingly overwhelmed by “horror of my other self” (Tusitala Edition 72). As such it is one of the most important occurrences of the mirror image in the late nineteenth century.2 It is characteristic of Macauley’s illustrations that Hyde’s frontside is not shown in the mirror. We only see Jekyll looking agonized at his other self in the mirror. Macauley created a tradition of Jekyll before the mirror, a motif that recurs ever and again in illustrations of Stevenson’s narrative, though undergoing marked changes, as we will see. [→ 257]

Illustrations of Jekyll and Hyde and the Concept of the Meme

Looking at illustrations of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde in a diachronic perspective, a significant cultural phenomenon can be observed, which can be explained by referring to the concept of the meme. The term was coined by Richard Dawkins in The Selfish Gene, who defined memes as units of cultural information. According to Dawkins, memes are related to genes. They involve a biological or evolutionary development or, to put it simply, a change of the human brain. Memes are supposed to be replicators like genes. Central terms in Dawkin’s theory are “replication” and “imitation.” As examples of memes he mentions “tunes, ideas, catch-phrases, clothes fashions, ways of making pots or of building arches” (192). As distinct from my project, he and his follower Susan Blackmore (The Meme Machine) are not concerned with literature at all. Significant forays into the field of literary memes, based on the concept of cultural memory, are undertaken by Ziva Ben-Porat.

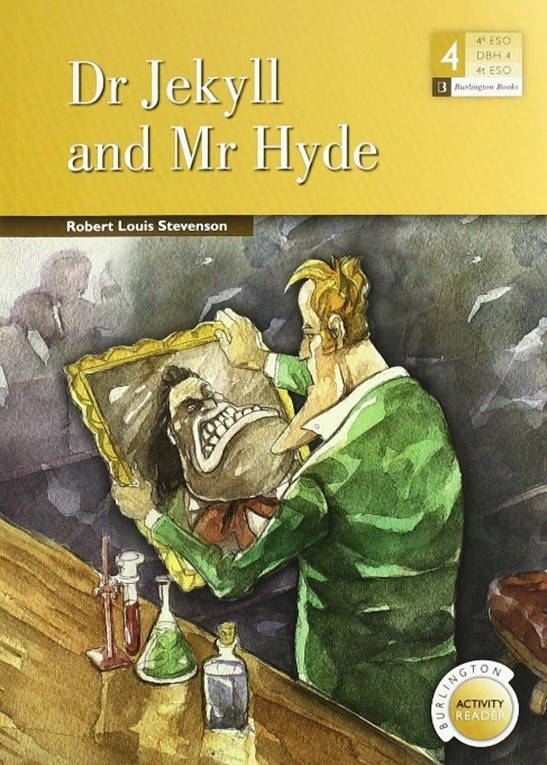

Fig. 7: Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. Spanish Edition, ES04. Burlington Books, 2011.

For my purposes, the opposition of imitation and emulation, which has a tradition since Renaissance poetics, is useful. Just as memes replicate and outdo previous memes, new illustrations imitate, change and outdo earlier representations. If we look, for example, at the use of the [→ 258] image of the mirror in illustrations of Jekyll and Hyde, we can observe the face of Hyde, which Macauley did not pictorialize, getting increasingly prominent. In an exorbitant example (fig. 7), Jekyll is aghast at seeing in the mirror his terribly distorted face with a grotesquely oversized set of teeth. As we have seen, Macaulay avoids such a self-confrontation, a face-to-face meeting of Jekyll and Hyde in the mirror. And the author Stevenson, to return once more to the text for a moment, presents a different self-perception of Jekyll as Hyde than any of his illustrators: “And yet when I looked upon that ugly idol in the glass, I was conscious of no repugnance, rather a leap of welcome. This, too, was myself” (Tusitala Edition 61). As enthusiastic as one may be about the great variety of successful illustrations of Jekyll and Hyde, there is no denying the fact that they cannot attain the complexities and ambiguities of Stevenson’s representation of duality. Macauley knew why he was so reluctant to depict Hyde’s face.

The illustrations on the covers or frontispieces of the editions have to be looked at closely. They usually consist of the two names Jekyll and Hyde and a corresponding image. In Stevenson’s narrative we are, except for Dr. Jekyll’s concluding “Statement,” never confronted with the two figures together. Simultaneous presence of the doubles is ruled out, though there are moments when one of the two changes into the other as a consequence of drinking the potion. However, the cover illustrations have to deal with the already-mentioned problem that there is the title containing the names of two persons and a pictorial image of one person, which, in view of the story, just cannot represent the two persons named in the title and yet must somehow try to do justice to the fact that the two are one and the same person. This is an artistic challenge to which the illustrators have to rise. The illustrations focus on the correlation of fair and good on the one hand and of ugly and evil on the other. The classical ideal of kalokagathia, the fusion of good looks and moral excellence, and its implied inversion, the fusion of bad looks and bad morality, is not evoked by Stevenson. This may be the impression which the illustrations create, but this is definitely alien to Steven- [→ 259] son’s text which is much more complex than such a striking visual opposition may suggest. The cognitive and moral point of Dr. Jekyll’s dual existence is that it reflects divisiveness as a general feature of the human soul and particularly of the Victorian state of mind, which hides vice, debauchery and many other kinds of abuse and malpractice under a gentlemanlike exterior and perfect manners.

Let us now look at instances of the representation of duality which appear as memes, i.e. cultural replicators, particularly in covers and title pages of Stevenson’s narrative. It is a task of the illustrators to find ways of designing the object of their illustrations so as to suggest duality, the co-presence of two contrary sides of one and the same person which emerges as an aesthetic as well as an ethic dichotomy. The following example (fig. 8) actually contains two personages. It consists of a lightly sketched portrait of a man wearing a jacket and tie. His hair is thin, his eyes are closed, and he holds his face thoughtfully or just careless in his right hand. Over his left shoulder we see the upper half of a darkly sketched face with straggling black hair and the eyes wide open, looking pressingly at the other’s face. The devil is commonly depicted on the left shoulder, the angel on the right. The double portrait is an impressive attempt at a graphic visualization of two intertwined personages, one forcing himself on the other one.

Fig. 8: Der merkwürdige Fall von Dr. Jekyll und Mr. Hyde. Illus. Robert de Rijn. Ditzingen: Reclam, 2015.

[→ 260] The Origin of the Central Meme of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

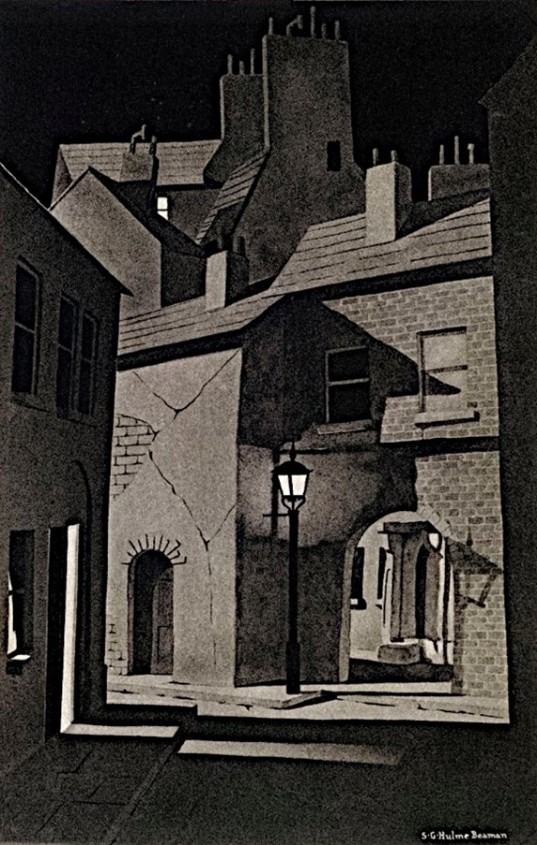

Fig. 9: “The Transformation” in The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde. Illus. S. G. Hulme Beaman. London: John Lane, 1930.

Fig. 10: The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde. Illus. S. G. Hulme Beaman. London: John Lane, 1930.

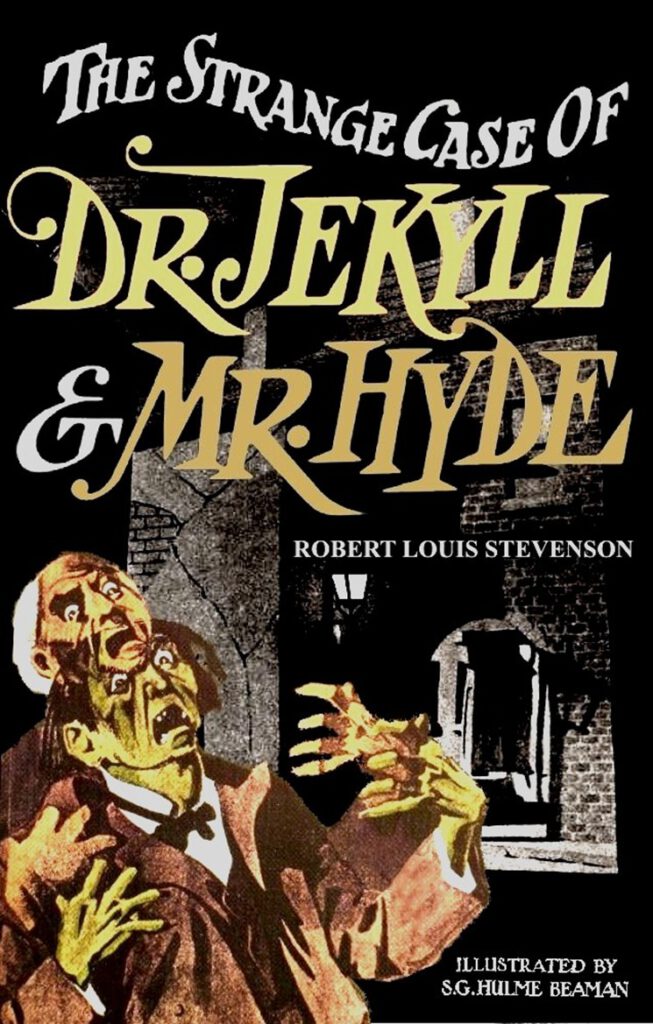

[→ 261] The most outstanding image or meme appearing in illustrations of Stevenson’s narrative is, of course, the image of the bipartite or divided or split face, which has spread over the whole world and acquired fame independent of Stevenson’s text. Before discussing examples of this image, we will turn to the intricate issue of its origin. I must admit that I do not know a solution to this knotty problem, but I wish to look at an illustrated edition of Jekyll and Hyde which may have paved the way for the meme. This is Hulme Beaman’s edition of 1930, one of the finest illustrated editions of Jekyll and Hyde ever to have been produced. Its cover is a collage of the two illustrations (figs. 9, 10) presented above.

Fig. 11: The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde (with the original illustrations by S. G. Hulme Beaman). London: John Lane, 1930.

The cover (fig. 11) renders a moment in the process of the protagonist’s metamorphosis in the lower left corner and a view of the city scenery in the background of the right-hand side with emphasis on the door through which Jekyll’s double passes. The human dimension of the illustration is represented in colour, while the elements of the city are displayed in black and white. This illustration is impressive in that [→ 262] it connects a horrible moment in the tragic story of a double self and the city in which it is inalienably situated.3 In the context of our argument, two aspects are of special significance. First, there is an extraordinary physical connectedness of the two figures to be noted. A sense is evoked of their being almost glued together. Though they are clearly two persons, their faces and hands seem to be overlapping, and they share signs of being extremely horrified. The interconnectedness of the two persons is pictorially expressed more intensely than in any earlier representation. This is again a supreme case of interfigurality in the context of duality. Second, the cover illustration cites the names of the “two protagonists” together with the illustration, thus combining language and picture, which is characteristic of memes. The illustration also integrates the title into the picture, with the elegantly curved line of the first four words and the straight letters of the names Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, whose colours are, a point not be overlooked, adapted to the images of the two persons (yellowish and greenish). With its combination of word and picture the cover set a precedent which inspired many to follow, vary and outdo it.4

The Bipartite Face as a Meme

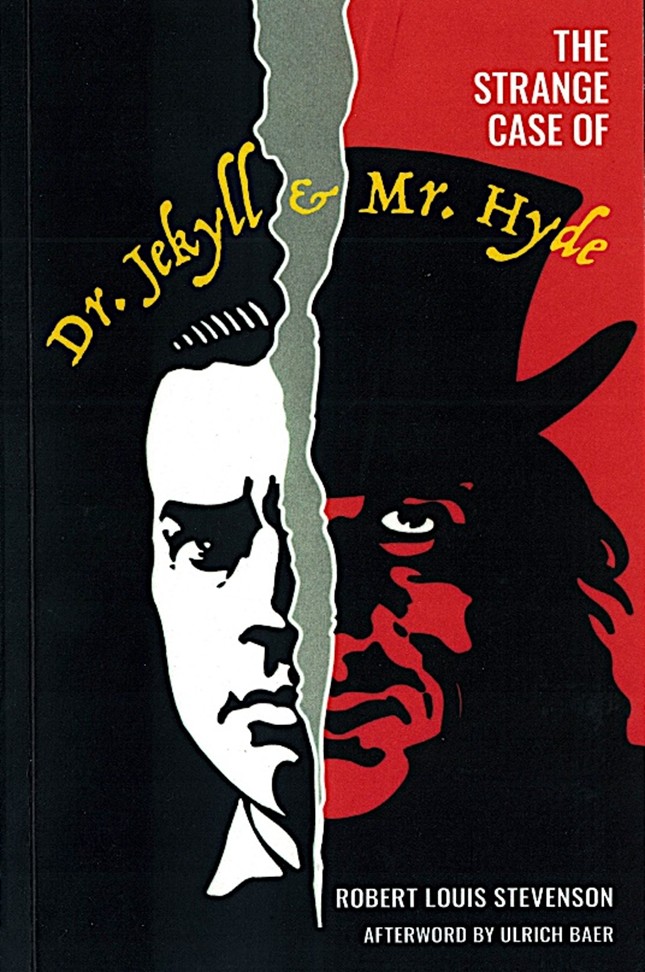

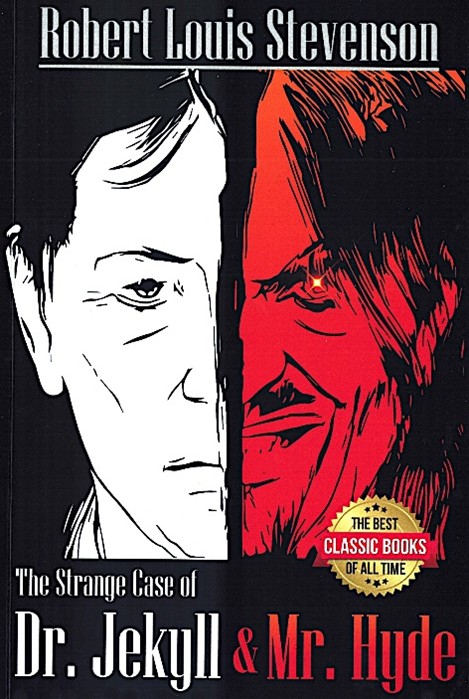

The following two covers (figs. 12, 13) show the split of a person marked by a rupture running right through the middle of the face, a deviation from realism common in memes such as the well-known “kilroy meme.” Interfigurality is here reduced to the representation of the face. The similarity of these images seems so strong that one may believe them not to have been produced independently. But the editions appeared in the same year, 2021, which makes plagiarism implausible, and upon closer inspection they reveal significant differences, e.g. as to the distribution of colour and the design of the faces. What they have in common is that the evil part of each, actually the right-hand side of the faces from the reader’s perspective, seems to be influenced by traditional images of demons and devils. I am not sure but there may be [→ 263] an allusion to Hitler’s face in the second image. The likeness of the faces represented in the two illustrations may be a characteristic of their features as memes. This does not exclude them from being parts of authentic editions, the first one with an excellent afterword by Ulrich Baer. What is astonishing in Baer’s edition is that it is a regularly printed product without illustrations which still has a meme on its cover.5 We thus can perceive that the meme, which essentially belongs to the digital culture, can even have an impact on a printed book. The line of my argument will be clearer in the next chapter, where I refer to Bob Kane’s Batman supervillain Two-Face which first appeared in August 1942, in Detective Comics #66 (“The Crimes of Two-Face”).

Fig. 12: The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Afterword Ulrich Baer. New York: Warbler Classics, 2021.

[→ 264]

Fig. 13: The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Illus. Dmitry Mintz. Wroclaw: Mr. Mintz Classics, 2021.

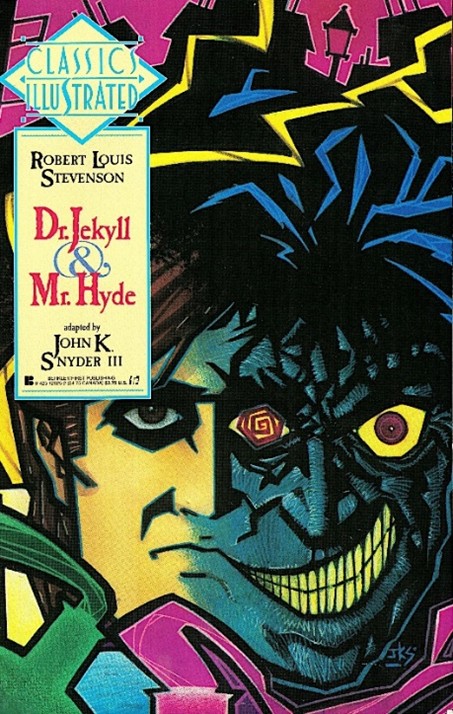

In the history of illustrations of Jekyll and Hyde examples such as these represent an iconographic innovation of profound cultural significance. According to my knowledge, there are no precedents for this graphic constellation, neither in classical antiquity nor in the Middle Ages or modernity. In classical mythology there is double-faced Janus (Janus Gemini), God of beginning and end. He has two faces, but not a split face. In medieval sacral architecture there is a significant parallel in the statue of “Frau Welt” (“Dame World”), for instance in the cathedral of Worms (fig. 14). It is of alluring beauty and splendour when seen from the front, but from its backside it looks ugly, full of puss, vermin, toads and snakes. Contrary to this front-back opposition of the sacral statue, the dichotomic image of Jekyll and Hyde is side by side, caused by a rupture in the representation of the face. The near-simultaneity of the strongly similar illustrations of Jekyll and Hyde excludes the probability that one of them can be taken as the origin of the new iconographic tradition. Both of them have to be taken as memes, visual images in a row of replicated manifestations. The origin of the iconographic split face is unclear. An interesting picture in this context is, for instance, the eerie cover page of a 1990 comic by John K. Snyder (fig. 15) which is marked by a division of a face into a rather normal part [→ 265] and a larger grotesque, phantasmagorical part, which seems to explode with energy and demonic glee and extends to yellow and blue zigzag lines in the sky of the city. Actually, the picture represents one face with a half face glued to it. The illustrator is on the way to the split face.

Fig. 14: Frau Welt. South portal of Worms Cathedral, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. Photo by Jivee Blau. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Worms-_Dom-_S%C3%BCdportal-_Frau_Welt_10.8.2010.jpg

Fig. 15: Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. Classics Illustrated. Adapted and illus. by John K. Snyder, TM and © First Classics, Inc. Chicago: Berkley, 1990.

[→ 266] A Note on Batman and Two Faces

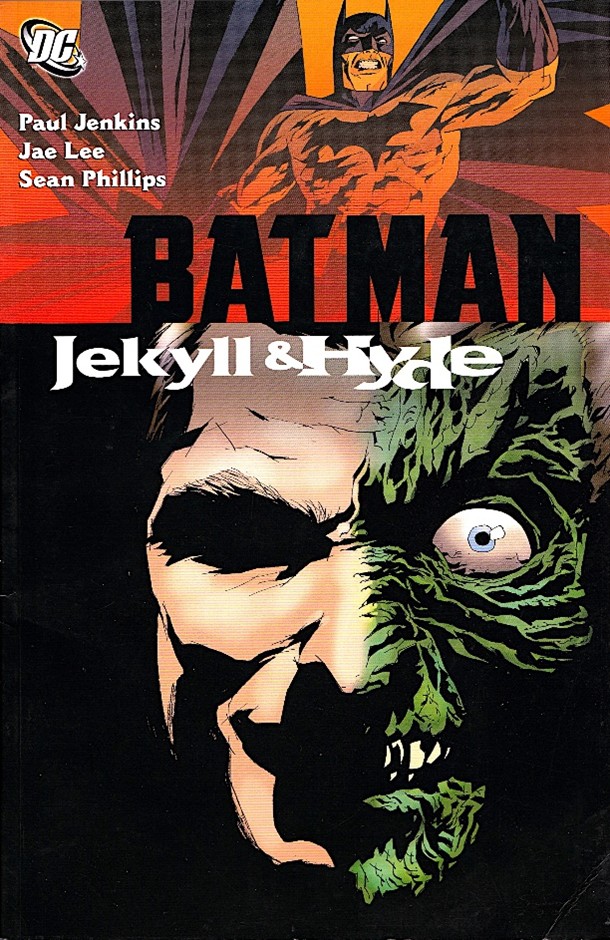

A decisive influence on the split-face illustrations of Jekyll and Hyde was exerted by the Two-Face images in the Batman series, which itself was influenced by the Stevenson heritage but produced a powerful new iconographic tradition with an incredibly rich effect especially in the world of the internet. Unfortunately, in this paper we can present only one from the vast number of remarkable instances.

Fig. 16: Batman: Jekyll & Hyde. Author Paul Jenkins, Illus. Jae Lee and Sean Phillips. Cover by Sean Phillips. London: Titan Books, 2008.

The chosen image (fig. 16) belongs to the Batman Jekyll and Hyde story which was written by Paul Jenkins. The story was illustrated by Jae Lee for the first half and by Sean Phillips for the second half. It was published from June 2005 to November 2005 in the comic book series Batman: Jekyll and Hyde. The story deals with the psychology behind Harvey Dent’s split personality. “Two-Face” harbours two souls, each bent on the other’s destruction. The attempt to extricate the evil component from the dual personage fails with dreadful consequences. The [→ 267] story was inspired by Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde but pursues its own agenda. The wikipedia page cites a book by Bob Kane, in which he is supposed to have named Stevenson as a direct inspiration for Two-Face. I believe this proposition to be plausible, though I cannot access the book to check: “In creating Two-Face, Kane was inspired by the 1931 adaptation of the Robert Louis Stevenson story The Strange Case of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, which Kane described as a ‘classic story of the good and evil sides of human nature,’ and was also influenced by the 1925 silent film adaptation of Gaston Leroux’s novel The Phantom of the Opera.” A comprehensive investigation of the relation between Jekyll and Hyde and “Two-Face” cannot be attempted here, and the explosive augmentation of the double-face image all over the world, which coincides with Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, would simply be impossible.

Imitation, Emulation, Innovation

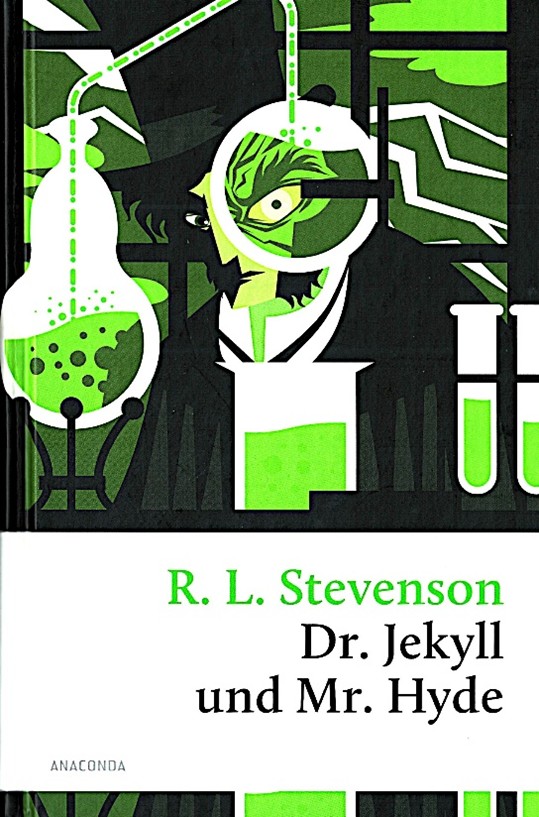

What the illustrations adduced so far share is the principle of imitation which is particularly conspicuous in book covers. Another feature memes have in common is emulation, the permanent attempt of illustrations to outdo their precursors, a general feature of memes in which Dawkins finds an evolutionary principle. Emulation implies creativity, the effort to enhance the graphic achievements of previous illustrations. Emulation can also result in innovation. What can be observed here is the return of the classical productive relation of imitation (imitatio) and emulation (aemulatio) under new cultural conditions. The following picture (fig. 17) shows a book cover which focusses on the scientific aspect of the interrelation between Jekyll and Hyde, the way the chemical liquid is conducted into Jekyll’s brain from a flask via a tube. The respective levels of the liquid in the protagonists are indicated by the various fillings of test tubes. The image also appears to repeat the magnification of Hyde that was observable in earlier illustrations—the monster appears to be re-conceived, in a metamorphosis, so large as to be more [→ 268] threatening. The image imitates earlier representations of the scientific aspect of the story of Jekyll and Hyde and at the same time outdoes them in an unprecedented way. It is an innovative image which would reward closer examination. Behind the chemical and cerebral operation in the foreground, the figure of Hyde is looming in the background. This is actually a composite meme, consisting of the metamorphosing scientist in the foreground and the result of the metamorphosis as a dark shadow in the background.

Fig. 17: Robert Louis Stevenson. Dr. Jekyll und Mr. Hyde. © 2005, Anaconda, Munich, in the Penguin Random House Publishing Group.

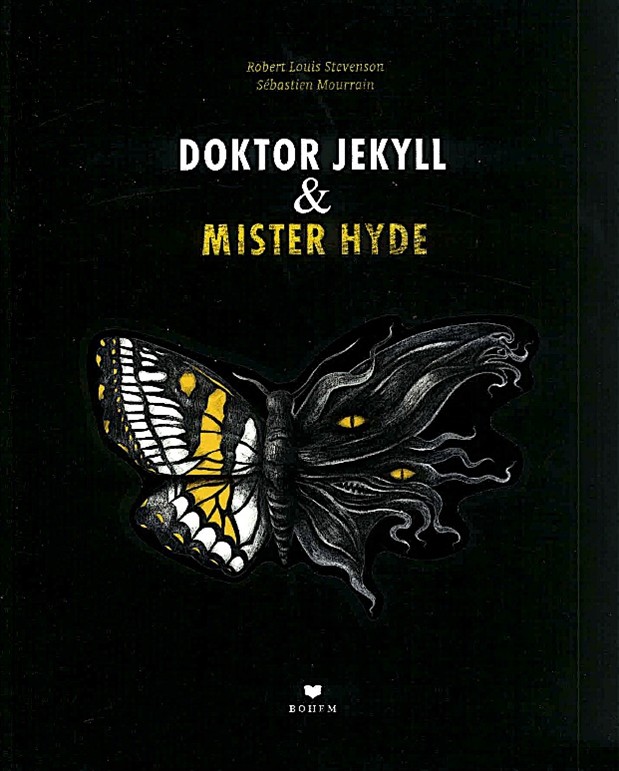

The next illustration (fig. 18) from a German large-format edition shows a butterfly as a cover image with two wings, one white, with a beautiful yellow and black pattern, and the other black, looking like a ragged black mask with two yellow eyes and a suggested row of teeth. This illustration, which looks like an object of art, is innovative in that it shifts the representation of the two opposite sides of a person’s face into a purely aesthetic sphere. It is of great interest to investigate the ways in which the myth of the double existence of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde traversed eras and cultures and produced remarkable artistic and [→ 269] literary creations, which in spite of their uniqueness cannot be detached from their point of origin, Stevenson’s ingenious tale.

Fig. 18: Cover illustration by Sébastien Mourrain. Doktor Jekyll & Mister Hyde. Münster: Bohem P, 2017.

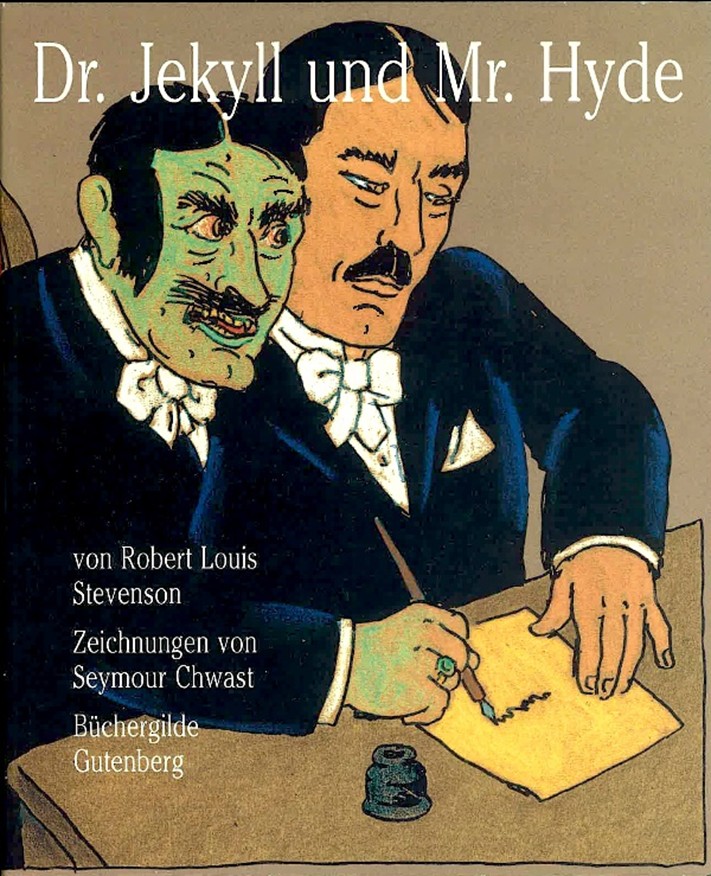

Another highly inventive modern illustration shows a picture from a further remarkable large-format edition which offers pictures by Seymour Chwast (1995). The cover illustration (fig. 19) differs from the tradition of Jekyll and Hyde memes in that it presents two separate personages, who are, however, like Siamese twins, related by sharing just two hands. It is important that this illustration goes back directly to Stevenson’s text. The person who represents Hyde is shown in the process of writing on a sheet of paper which is held fast by the other’s hand. Hyde has taken over Jekyll’s hand and is writing for him. This illustration refers to the testament which Jekyll is made to write in the tale in favour of Hyde. The illustrator has obviously had a close look at the text. His picture throws light on one of the important moments of the story’s action. The fact that here the two protagonists appear side by side deviates from the text, which hardly ever presents them together. Yet it follows the text in that it goes back the questions of Dr. Jekyll’s will. [→ 270]

Fig. 19: Cover illustration by Seymour Chwast. Dr. Jekyll und Mr. Hyde. Frankfurt a. M.: Büchergilde Gutenberg, 1995.

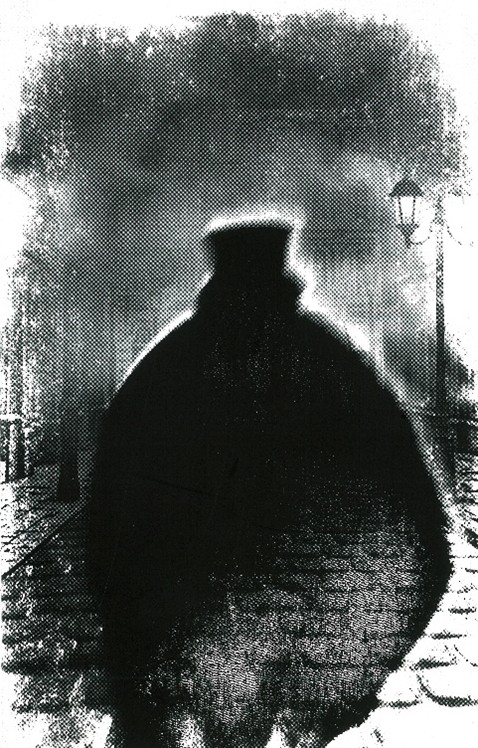

By way of conclusion, this essay will look at just one of the many remarkable illustrations of Stevenson’s city (fig. 20). As a city tale Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is placed strongly in the tradition of Edgar Allan Poe, specifically of his story “The Man of the Crowd” (1840), which is also set in the City of London. Stevenson was familiar with Poe. The picture represents a figure as a dark shape which blurs into the darkness of the city. The darkness of the figure is accentuated by the brightness of its edge in the picture’s upper half, caused by the light of the streetlamp. The amalgamation of the figure with the city is made visible by the fact that the cobbled pavement of the street recurs in the dark shape of the figure. Hyde is visualized as a spawn of the city. The meme outdoes all representations of Hyde as a wanderer through the city at night. [→ 271]

Fig. 20: Der seltsame Fall des Dr. Jekyll und Mr. Hyde. German Edition. Illus. Tracy Tomkowiak. N.p.: Alden P, 2023.

Conclusion

Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde has had an amazing reception by illustrators and artists who succeeded in capturing the atmosphere of the city of London, significant architectural details, the physiognomies of participants in the action, the shadowy persons who move through the city at night, carrying with them their secrets, and the horrible crimes which are committed. In particular, they highlight motifs that are relevant to the issue of duality such as the reflection in a mirror and the shadows thrown by persons, aspects to be taken up by later illustrators. The magnificent edition of 1930 with illustrations by S. G. Hulme Beaman represents a significant turning point in the history of illustrated editions of Jekyll and Hyde, first, by the intensity of the depiction of an extreme connectedness of the two bodies of the dual personage, and, second, by the cover illustration which, with the association of the names of the two actors and the illustration, suggests a mixed identity. This is the birth of the meme of Jekyll and Hyde, which has achieved worldwide dissemination, augmented most strongly by the [→ 272] internet. The meme is a phenomenon of popular culture. Without this culture, the image of Jekyll and Hyde could never have had its astonishing dissemination. The triad of the constitutive elements of the meme—imitation, emulation, innovation—made it possible that, side by side with the multiplicity of mainly replicatory instances, the meme could add to the richness of one of the most enduring modern myths.

Works Cited

Abnett, Dan, Andy Lanning. Batman: Two Faces. Burbank, CA: DC Comics Elseworlds, 1998.

Ben-Porat, Ziva. “The Western Canon in Hebrew Digital Media.” Neohelicon 36 (2009): 503-13.

Blackmore, Susan. The Meme Machine. Oxford: OUP, 1999.

Cook, Jessica. “The Stain of Breath Upon a Mirror: The Unitary Self in Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.” Criticism: A Quarterly for Literature and the Arts. 62 (2020): 93-115.

Dawkins, Richard. The Selfish Gene. New York: OUP, 1976.

Esther, Theodora. The Monster in the Mirror: Late Victorian Gothic and Anthropology. Dissertation Boston U, 2012.

Jenkins, Paul. Batman: Jekyll & Hyde. Illus. Jae Lee and Sean Phillips. London: Titan Books, 2008.

Kane, Bob, and Tom Andrae. Batman and Me. Forestville, CA: Eclipse Books, 1989.

Mills, Kevin. “The Stain on the Mirror: Pauline Reflections in The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.” Christianity and Literature 53 (2002): 337-48.

Müller, Wolfgang G. “Literary Figure into Pictorial Image: Illustrations of Don Quixote Reading Romances.” Literaturwissenschaftliches Jahrbuch 55 (2014): 239-69.

Müller, Wolfgang G. “Interfigurality: A Study on the Interdependence of Literary Figures.” Intertextuality. Ed. Heinrich F. Plett. Berlin: de Gruyter, 1991. 101-34.

Niederhoff, Burkhard. “Die Metamorphosen eines Puritaners.” Nachwort zu Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Frankfurt a. M.: Büchergilde Gutenberg, 1995. 130-39.

Stevenson, Robert Louis. Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. Spanish Edition. N.p.: Burlington Books, 2011.

Stevenson, Robert Louis. Dr. Jekyll und Mr. Hyde. Illus. Seymour Chwast. Frankfurt a. M.: Büchergilde Gutenberg, 1995.

Stevenson, Robert Louis. Der merkwürdige Fall von Dr. Jekyll und Mr. Hyde. Trans. Mirko Bonné. Illus. Robert de Rijn. Ditzingen: Reclam, 2015.

Stevenson, Robert Louis. Der merkwürdige Fall des Dr. Jekyll und Mr. Hyde. Trans. Mirko Bonné. Ditzingen: Reclam, 2020.

Stevenson, Robert Louis. Der seltsame Fall des Dr. Jekyll und Mr. Hyde. Munich: Anaconda, 2005. [After an anonymous trans. of 1925.]

Stevenson, Robert Louis. Der seltsame Fall des Dr. Jekyll und Mr. Hyde. Illus. Tracy Tomkowiak. N.p.: Alden P, 2023.

Stevenson, Robert Louis. Der seltsame Fall des Doktor Jekyll & Mister Hyde. Trans. Nils Aulike. Illus. Sébastian Mourrain. Münster: Bohem P, 2017. Rpt. of Docteur Jekyll & Mister Hyde. Toulouse: Edition Milan, France, 2015.

Stevenson, Robert Louis. Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1886.

Stevenson, Robert Louis. The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde. Fables. Other Stories & Fragments. Tusitala Edition. London: Heineman, 1924.

Stevenson, Robert Louis. Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde and Other Tales. Ed. Roger Luckhurst. Oxford World’s Classics. Oxford: OUP, 2006.

Stevenson, Robert Louis. The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Ed. and afterword Ulrich Baer. New York: Warbler Classics, 2021.

Stevenson, Robert Louis. Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Ed. Deborah Lutz. New York, London: Norton, 2021.

Stevenson, Robert Louis. The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Illus. Charles Raymond Macauley. New York: Scott-Thaw Company, 1904.

Stevenson, Robert Louis. The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. Illus. Charles Raymond Macauley. Orinda, CA: SeaWolf P, 2023. [Text and illus. from the 1904 Scott-Thaw ed.]

Stevenson, Robert Louis. The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Illus. Dmitry Mintz. Mr. Mintz Classics: Wroclaw, 2021.

Stevenson, Robert Louis. The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Illus. S. G. Hulme Beaman. London: John Lane, 1930.

Stevenson, Robert Louis. Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. Illus. Lou Cameron. Newbury: Classics Illustrated, 2016.

Stevenson, Robert Louis. Dr Jekyll & Mr Hyde. Classics Illustrated. Adapted by John Snyder. Chicago: Berkley, 1990.

Stevenson, Robert Louis. Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Usborne English Readers Level 3. Illus. Alessandro Valdrigi. London: Usborne Publishing Ltd., 2021.

“Two-Face.” Wikipedia, 27 June 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Two-Face. 14 Aug. 2025.

Wagner, Peter. “The Nineteenth-Century Illustrated Novel.” Handbook of Intermediality. Literature—Image—Sound—Music. Ed. Gabriele Rippl. Berlin: de Gruyter, 2015. 378-400.