by Laurie Atkinson

The Garlande or Chapelet of Laurell by John Skelton is five hundred years evergreen. In 1523, this remarkable poem about Skelton’s elevation to the court of Fame was published in London by Richard Faques. Mostly the preserve of early modern scholars, Skelton is best known as the writer of satires and invectives at the court of Henry VIII – most famously against the king’s powerful minister, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, who he calls ‘the bochers dogge’ (Why Come Ye Nat to Court?, line 298), among other things. But in the Garlande, Skelton’s subject is himself; or rather, a laureate version of himself, named ‘Skelton Poeta’ in Faques’ edition. The narrative is framed as a dream, with the action moving between the Yorkshire castle of the Countess of Surrey and a series of allegorical tableaux. An overheard conversation between Dame Pallas (Minerva) and the Queen of Fame about whether ‘in my courte Skelton shulde have a place’ (line 59) is followed by a procession of ‘poetis laureat’ (line 324) from antiquity to the recent past, ending with the three great medieval English poets, John Gower, Geoffrey Chaucer, and John Lydgate. The dreamer is introduced to Fame’s registrar, ‘Occupacyon’, who holds a ‘boke of remebrauns’ containing all of Skelton’s works. They visit the Countess of Surrey and her ladies in their chamber, who weave for Skelton ‘A cronell of lawrell with verduris light and darke’ (line 775) – a laurel crown like those awarded in ancient Greece and Rome, from which the Garlande or Chapelet of Laurell takes its name. The poem ends in the palace of Fame, where ‘Occupacyon’ recites before Fame and her court a long list of Skelton’s works – many of which seem to have been invented – before the dreamer is awoken by cries of ‘Triumpha, triumpha!’ and the shaking of the heavens. Skelton’s fame is confirmed.

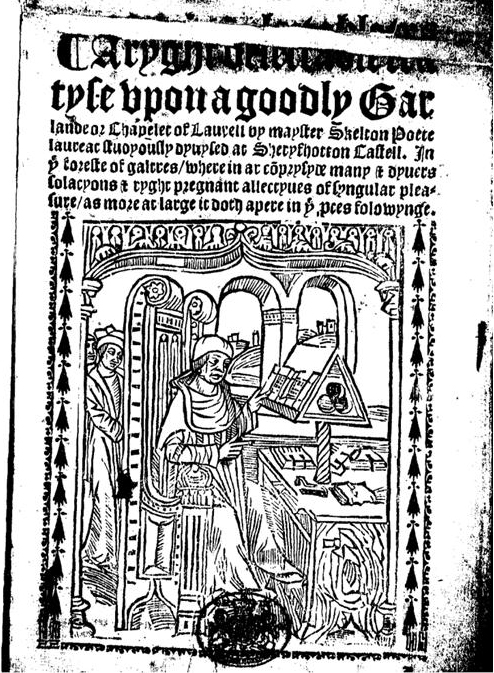

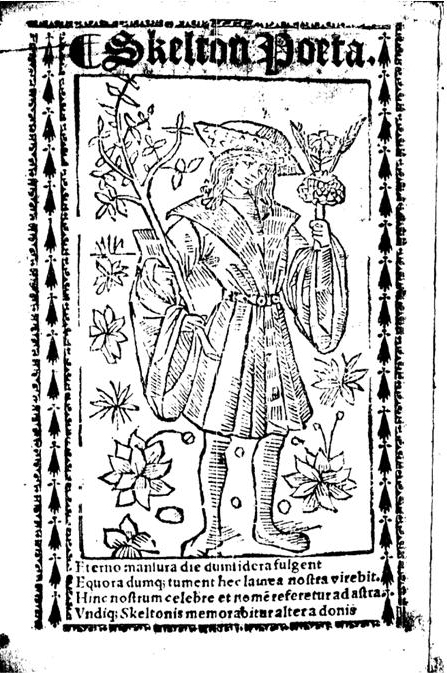

Skelton’s Garlande resists easy interpretation – is it a serious claim for immortality through art unprecedented in English poetry, or a playful parody of earlier dream visions, satirising the vogue for ‘poet laureates’ at Renaissance courts and universities? Even its date is difficult to determine: the colophon in Faques’ edition says that it was ‘Inprynted […] The yere of our lorde god .M.CCCC.xxiii. The .iii. day of Octobre’ – that is, 3 October 1523; but the Countess of Surrey and her ladies belong to the mid-1490s, and much of the poem may have been written about that time. The recto and verso of Faques’ titlepage present quite different images of Skelton (see below): on the recto, he is a venerable author seated in his study, surrounded by books; but on the verso, the figure with the heading ‘Skelton Poeta’ is a symbol of vitality and renewal – a symbol, indeed, of April. It is in the spirit of eclecticism of Skelton and Faques, and the easy blending of fact and fiction in the Garlande, that I have chosen to commemorate the poem not in October, when Faques printed it, but in April, the month of renewed life which the titlepage verso evokes.

John Skelton, A ryght delectable treatyse upon a goodly gralande or chapelet of laurel… (London: Richard Facques, 1523) STC 22610, titlepage, recto and verso. London, British Library, General Reference Collection, 82.d.25 (© British Library Board. Images published with permission of ProQuest. Further reproduction is prohibited without permission.)

How did Skelton arrive at his idealised self-construction in the Garlande? John Skelton (c.1463–1529) really was a poet laureate, but not the royally appointed kind which we know today. In 1493, the University of Cambridge pronounced that Conceditur Johanni Skelton poete in partibus transmarinis atque oxonie laurea ornato ut aput nos eadem decoraretur (‘John Skelton, poet, having been crowned with laurel in parts beyond the sea and at Oxford, shall receive the same decoration from ourselves’, Grace-Book B I: 54). The laureateship described was a degree in rhetoric rather than an award for poetry. By around 1496, Skelton was of sufficient reputation as a scholar and rhetorician to be appointed tutor to Prince Henry, the future Henry VIII. Skelton was replaced as Henry’s tutor in 1502; but when he returned to court ten years later was appointed orator regius (‘orator of the king’) by his former student and seems to have performed a role approximating an official spokesperson of the king. Skelton was never granted the title of ‘poet laureate’ like his contemporary at court, Bernard André (Campbell II: 62); yet undeterred, he still referred to himself as such in a number of poems besides the Garlande:

It semyth nat thy pyllyd pate

Agesnt a poyet lawreat

To take upon the for to scryve

(Agesnst Garnesche v.84, 90)

Skelton laureat

After this rate

Defendeth with his pen

All Englysh men

Agayn Dundas,

That Scottishe asse.

(Against Dundas, lines 19–20)

Why fall ye at debate

With Skelton laureate

Reputyng hym unable

To gainsy replycable

Opinyons detestable

Of heresy execrable?

(A Replycacyon, lines 300–01)

In each of these examples, Skelton invokes the laureate title as proof of his authority against detractors. The tone is caustic, belonging to court flyting or the poetic exchange of insults, but these were hardly the limit of Skelton’s laureate ambitions. A more elevated tone is assumed in the Latin materials which often frame his English poems, for instance in Phyllyp Sparowe, a mock elegy for the death of a young girl’s pet sparrow:

Per me laurigerum Britonum Skeltonida vatem

Laudibus eximiis merito hec redimita puella est

Formosam cecini, qua non formosier ulla est;

Formosam potius quam commendaret Homerus.

Sic juvat interdum rigidos recreare labores,

Nec minus hoc titulo tersa Minerva mea est.

Rien que playsere

Through me, Skelton, the laureate poet of Britain, this girl is deservedly crowned with choice praises. I have sung of the beautiful girl than whom there is no one more beautiful; a beautiful girl preferable to any Homer might commend. Thus, it is pleasant occasionally to refresh hard labours; nor is my wisdom [Minerva was the Roman goddess of wisdom] any less brief than this inscription. Only to please.

(Phyllyp Sparowe, lines 1261–62, 1265–66)

Here, we can see many of the elements which make up Skelton’s self-construction in the Garlande: the suggestion that his laureate title confers on him the authority of ‘the poet of Britain’; the capacity of his poetry to exalt its subjects – even if the subjects themselves (a young girl, a dead sparrow, an ex-tutor to a prince) seem incongruous with Skelton’s praises; and the recurring image of the evergreen laurel, betokening the rejuvenating power of poetry.

These imaginative associations, traversing the range of connotations of the laureate title, are nowhere more densely concentrated than in the image of Skelton Poeta on the verso of the Garland’s titlepage. Like many of the illustrations in early English printed books, the design of the Skelton Poeta woodcut is not original to this edition. It is a copy from a series of illustrations of the occupations of the months, which appeared in the Compost et kalendrier des bergeres published in Paris in 1499 (Erler 20). There, it is the illustration for April and Spring – a young man holding a large flower in his left hand and a tree branch in his right. The connection between a branch-bearing figure – understood to be a laurel – and the laureated poet is fairly obvious. But in conjunction with the Latin verse which is printed below, the image articulates the rejuvenating as well as the exalting power of poetry, as the laurel is made to denote renewed life as well as eternal fame:

Eterno mansura die dum sidera fulgent,

Equora dumque tument, hec laurea nostra virebit:

Hinc nostrum celebre et nomen referentur ad astra,

Undique Skeltonis memorabitur alter Adonis.

While the stars shine remaining in everlasting day, and while the seas swell, this our laurel shall be green; our famous name shall be echoed to the skies, and everywhere Skelton shall be remembered as another Adonis.

The lines are ostentatiously learned, with echoes of Virgil’s Aeneid III.86 (mansura sidera), Ovid’s Ex PontoI.xii.54 (aequora tument), and Horace’s Ode’s II.xvi.4 (sidera fulgent) (Brownlow 175). They are in keeping with the image of the author in his study on the recto of Garlande’s titlepage; yet the choice of Adonis as Skelton’s mythical counterpart points to a different aspect of the poet’s art. Loved by Venus for his beauty, the youth Adonis was fatally wounded by a wild boar and bled to death in Venus’s arms. As she mourned her lover, Venus caused anemones to grow wherever his blood fell and declared a festival on the anniversary of his death (Ovid X.716–39). Together, the Skelton Poeta woodcut and alter Adonis verse transform Skelton the university laureate and orator regius into Skelton Poeta the bearer of vitality. As Mary C. Erler explains,

Skelton here conflates the mythic Adonis, the French woodcut’s branch-bearing figure, and himself, the living poet. […] Despite Skelton’s monumental vanity, centrally displayed in Garlande of Laurell, it is Adonis as embodiment of vegetative renewal, rather than of seductive beauty, whom the poet intends when he speaks of himself as ‘alter adonis’. (Erler 21, 22)

We must judge for ourselves whether Skelton’s Garlande constitutes a display of ‘monumental vanity’. It is certainly a testament to the ingenuity and inventiveness of an underappreciated English poet – ironic, given the pronouncement of his Queen of Fame – and the eclecticism of early English print. From the seedbed of biography, humanist learning, and iconography, the Garlande yields a poet and an idea of English poetry at once transcendent and sui generis. Five hundred years later, the Garlande or Chapelet of Laurell remains a book which deserves ‘remebrauns’.

Works Cited

Bateson, Mary (ed.). Grace-Book B: Containing the Proctors’ Accounts and Other Records of the University of Cambridge for the Years 1488–1511. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2 vols.

Campbell, William, Materials for a History of the Reign of Henry VII: From Original Documents Preserved in the Public Record Office. London: Longman, 1873. 2 vols.

Compost et kalendrier des bergères. Paris: G. Marchand, 1499.

Erler, Mary C. ‘Early Woodcuts of Skelton: The Uses of Convention’. Bulletin of Research in the Humanities, vol. 87, 1986–87, pp. 17–28.

Ovid. Metamorphoses, 3rd edn, translated by Frank Justus Miller, revised by G. P. Goold. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1977–84. 2 vols.

Skelton, John. The Book of the Laurel, edited by F. W. Brownlow. Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1990.

Skelton, John. The Complete English Poems of John Skelton, rev. ed., edited by John Scattergood. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2015. All quotations from Skelton and translations of his Latin verse are from this edition.

Skelton John. A ryght delectable treatyse upon a goodly garlande or chapelet of laurel…. London: Richard Faques, 1523.