by Eva Marik

Have you ever read the novels of Anthony Trollope? They precisely suit my taste, – solid and substantial, written on the strength of beef and through the inspiration of ale, and just as real as if some giant had hewn a great lump out of the earth and put it under a glass case, with all its inhabitants going about their daily business, and not suspecting that they were being made a show of. And these books are just as English as a beef-steak. Have they ever been tried in America? It needs an English residence to make them thoroughly comprehensible; but still I should think that human nature would give them success anywhere. (Hawthorne qtd. in Trollope, Autobiography 167)

Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote these lines as early as 1860, which is why they could not refer to Anthony Trollope’s novel The Way We Live Now, published in July 1875. Nevertheless, as Jody Griffith notes, they aptly describe this later title in Trollope’s oeuvre as much as his earlier ones (153). Its narrative mode, for example, creates a sense of distant yet accurate perception of a teeming “lump […] of earth” (Hawthorne qtd. in Trollope, Autobiography 167). The extradiegetic and omniscient narrator of The Way We Live Now invites readers to gather around Hawthorne’s metaphorical glass case and observe the lives of various people in 1870s London and the surrounding countryside. Frequently, the narrator explicitly mentions the reader (for example, “let the reader be introduced to” [Trollope, The Way 3] and “it is hoped that the reader need hardly be informed that” [678]) and fictional letters interrupt the narrative with more prominence and versatility than is typical in contemporary writing (Sirota 105). The former narrative strategy creates a sense of the reader looking in from the outside and the latter suggests an undisturbed inside to be perceived. Thus, despite a high degree of mediation and clear distancing of both the narrator and the reader from the characters, The Way We Live Now feels “real” and “solid” (Hawthorne qtd. in Trollope, Autobiography 167).

Too real, perhaps, and too close for comfort, which may explain why initially, The Way We Live Now was one of Trollope’s less successful publications. Robert McCrum, who gives evidence to the novel’s recent rise in critical appreciation by including it in a series titled The 100 Best Novels, explains that

the publishers Chapman & Hall had […] made a contract with Trollope (an outright sale for £3,000) for The Way We Live Now, securing serialisation as well as volume rights. […] The novel did badly in serial form, from February 1874 to September 1875. A two-volume edition was published in July 1875, pre-empting the last stages of the serialisation.

Griffith moreover cites some negative reviews which appeared at the time arguing that

[t]his lack of appreciation seems at least in part to reflect what its reviewers identified as its bad narrative manners. […] The deictic “we” and “now” of the title seem to cast aspersions […]. They [the characters] are not us, these reviewers complain, and Trollope’s title is rude to suggest they are. (Griffith 146-47)

The characters are indeed flawed and unable to form a harmonious social whole because they each subscribe to different notions of value and status hierarchy. Trollope’s novel reflects a time of accelerating social transformations: the aristocracy’s landownership morphed from a source of revenue to a burden, physical money was increasingly being replaced by intangible capital, and large-scale capitalist ventures – such as infrastructure projects – and financial speculation made men wealthier faster than the landed gentry could hope to become. The glass case covering the particular lump of earth Trollope is examining suddenly seems “permeable” (Griffith 153) and its contents churned up as new ways of life intrude. The readers are made to sit and watch – and, as Griffith argues, for a purposefully long and uncomfortably drawn-out period (162) – as all the inhabitants go about their daily business with incongruent and colliding agendas.

In The Way We Live Now one character in particular prompts a kaleidoscope of contemporary attitudes towards new forms of wealth and power: Augustus Melmotte. Melmotte appears to be shockingly rich as a result of unsavoury business dealings in continental Europe which cave in on him eventually. Before his repeated financial collapse, this time in England, the elite in London is in uneasy awe of him. There is, to name but one example of the reactions Melmotte triggers, a chapter in which the patriarch of the Longestaffe family meets him to be advised about his own finances. Longestaffe, a squire with “aristocratic bearing” (Trollope, The Way 101) and pecuniary troubles, is described as one of those men who “think that if they can only find the proper Medea to boil the cauldron for them, they can have their ruined fortunes so cooked that they shall come out of the pot fresh and new and unembarrassed” (100). Longestaffe (misguidedly) deems Melmotte to be able to fulfil Medea’s promise, and nevertheless believes himself superior – as the narrator notes with some humour – because of his “land, and family title-deeds, and an old family place, and family portraits, and family embarrassments, and a family absence of any useful employment” (101). Accordingly, as Nicolas Tredell points out, the unsatiable “Melmotte only rises so high because of the greed of people who, in Trollope’s view, should know better—particularly the English aristocracy” (206). It is unsurprising, then, that readers neither sought to be included in a group of people considered quaint, easily duped, and out-of-date, nor in a group of lying, greedy, and cut-throat capitalists.

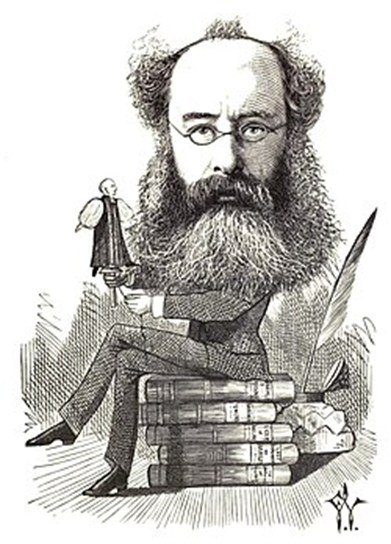

Anthony Trollope by Frederick Waddy

Uncomfortable truths – that, however, “may ultimately need saying” (Griffith 163) – are levelled at everyone, be they capitalists, aristocrats, members of the working class or men of the church, and Trollope does not shy away from criticising his own profession as well. In fact, the very first character to appear is Lady Carbury, who sees herself as “a woman devoted to Literature, always spelling the word with a big L” (Trollope, The Way 3). Lady Carbury is explicitly uninterested in producing anything transcending monetary value. To her, writing is but a means to the end of gaining social recognition and making money. This money is spent, in turn, to cover her son’s extravagant lifestyle and to allow him to join in the competition for Melmotte’s daughter’s hand in marriage – a marriage through which considerable wealth can be gained. Thus Literature becomes firmly embedded in an economic system that translates everything into money and holds nothing sacred: in Trollope’s London women are expected to marry for wealth or because they bring it; wealth is made through speculation; speculation leads to ruin, but ruin waits for those, too, who cling to old values. Maybe here, as well as in Trollope’s talent for humorously conveying what feels real, lies the reason why The Way We Live Now appeals to “human nature […] anywhere” (Hawthorne qtd. in Trollope, Autobiography 167), why it became popular during the 1980’s greed culture (Tredell 206), and why it is so relevant in the present day. As the twenty-first century closes its first quarter, ever new forms of commercialisation intrude into the arts and people’s lives (for example through AI, [see Erickson]). As global economic systems shift, the way we live is marked by new lines of power and heightened precarity. In these times, Trollope offers a discerning account of a parallel moment in social history while also offering an escape: to paraphrase Hawthorne, it allows the reader to consume an English beef steak’s worth of Victorian gossip.

Works Cited

Erickson, Kristofer. “AI and Work in the Creative Industries: Digital Continuity or Discontinuity?” Creative Industries Journal (2024): 1-20.

Griffith, Jody. “‘the less said the soonest mended’: Time and Etiquette in The Way We Live Now.” Nineteenth-Century Literature 78.2 (2023): 142-63.

McCrum, Robert. “The 100 Best Novels: No 22 – The Way We Live Now by Anthony Trollope.” The Guardian (17 Feb. 2014). https://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/feb/17/110-best-novels-way-we-live-now-trollope.

Sirota, Lauren. “Epistolarity and the Written Self: Letters in Anthony Trollope’s The Way We Live Now.” Studies in the Novel 53.2 (2021): 103-21.

Tredell, Nicolas. “An Anti-Greed Novel: Anthony Trollope’s The Way We Live Now.” Critical Insights: Greed. Ed. Robert C. Evans. Amenia, NY: Salem Press, 2019. 206-21.

Trollope, Anthony. Autobiography of Anthony Trollope. 1883. Auckland, NZ: The Floating Press, 2009.

Trollope, Anthony. The Way We Live Now. 1875. Ed. Robert Tracy. Indianapolis, IN: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1974.