“There’s Something Wrong Somewhere”: Disenfranchisement and Diegesis in David Goodis’s Down There

Robert Lance Snyder

Published in Connotations Vol. 30 (2021)

Abstract

Described by critics as a “poet of the losers” who masterfully portrayed the “economic struggles, in a truly Kafkaesque sense, of the underbelly of America during his time,” noir novelist David Goodis often used postwar Philadelphia as a microcosm of urban blight and disenfranchisement. At the same time his down-and-outers are typically unable to account for their predicaments. A brother of protagonist Eddie Lynn in Down There (1956) voices this bafflement when he says that “there’s something wrong somewhere.” A strong sense of the American Dream’s bankruptcy in the 1950s, coupled with the inability of Goodis’s characters to analyze it, lies behind his reliance on the narratological devices of internal dialogue, silent conversations, and indirect discourse to project the solipsistic repercussions of withdrawal from an alienating, ultimately hostile environment. Though defeated in the end, Goodis’s inner-city denizens are valorized by an attempt to escape from the prison-house of self and act on behalf of another person. Diegesis is central to this author’s exploration of the pervasive sense in Down There that “the sum of everything was a circle […] labeled Zero.”

In the expanded edition of a book first published in 1981, Geoffrey O’Brien described David Goodis as a “poet of the losers” who presented “traumatic visions of failed lives” (90). 1) The vague sense that [→ page 38] haunts all the protagonists in Goodis’s seventeen novels released between 1946 and 1967, most of which appeared as paperback originals issued by Fawcett Gold Medal and Lion Books, is what a character in Down There (1956) voices when he says that “there’s something wrong somewhere” (16). Although Turley Lynn hardly knows what he means by that statement, it encapsulates Goodis’s awareness that postwar America’s cultural trajectory, as reflected by Norman Rockwell covers of The Saturday Evening Post during the 1950s and early 1960s, had abandoned a sizeable number of its inner-city citizens. Agreeing with Woody Haut that this writer excels at “conveying urban angst” (21), Richard Godwin asserts that in his noir narratives Goodis ranks as “the master of class depiction and the demotic and economic struggles, in a truly Kafkaesque sense, of the underbelly of America during his time” (1). At the center of this author’s attention is the inability of his characters to realize the fabled American Dream given the scope of their disenfranchisement.

Goodis’s critique of the postwar period that crippled many of his countrymen’s prospects for a better life typically is conveyed through diegesis. This essay will argue, more specifically, that the narratological devices of internal dialogue, silent conversations, and indirect discourse in Down There allow Goodis to project the repercussions of withdrawal from an alienating, ultimately hostile world. Solipsism is the price that his down-and-outers pay for their dispossession, but though defeated in the end they are valorized by an attempt to escape from the prison-house of self and act on behalf of another person. Goodis’s characters, claims Nathaniel Rich, “are not genuinely cynical. Deep down each possesses a pitiful innocence that, at times, borders on idealism” (39). This trait separates his “losers, victims, drop-outs, and has-beens” from the usual orientation of stereotypical hard-boiled “heroes” who, when faced with a choice between involvement and non-involvement with others, usually opt, like Sam Spade in Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon (1930), for the latter (Schmid, “David Goodis” 157). In another essay the same critic contends that “Goodis’s protagonists spectacularly fail to maintain a tough masculine façade because they [→ page 39] are open, vulnerable, and desperate to break out of their isolation and establish a physical and/or emotional connection with another person” (“Different Shade” 156).

Framed at its outset from an omniscient point of view, the first chapter of Down There establishes Eddie Lynn as a refugee from a personally traumatic past. Unattached and with “no debts or obligations” (7), he now in his early thirties plays the piano six nights a week at a dive in the Port Richmond section of Philadelphia for a salary of thirty dollars plus tips. 2) While at the keyboard, directing “a dim and faraway smile at nothing in particular” (5), he improvises a “stream of pleasant sound that seemed to be saying, Nothing matters” (6). So reports the third-person narrator, but the text routinely embeds internal dialogue, as when the protagonist’s brother is seeking to evade enforcers from an underworld crime syndicate:

But you can’t do that, he told himself. You gotta get up and keep running. [...]

Maybe this is it, he thought. Maybe this is the street you want. No, your luck is running good but not that good, I think you’ll hafta do more running before you find that street, before you see that lit-up sign, that drinking joint where Eddie works, that place called Harriet’s Hut. (3)

Combined with indirect discourse, the passage alerts readers to the novel’s intradiegetic register. When Turley finds his way to Eddie’s place of employment, however, and appeals for his brother’s help, there ensues a contest of loyalties narratologically framed by an evocation of Eddie’s silent counsel to himself. Adamant about not getting involved in his brother’s plight—“Don’t look, Eddie said to himself. You take one look and that’ll do it, that’ll pull you into it. You don’t want that, you’re here to play the piano, period” (20)—he cannot shut himself off completely from Turley’s appeal to fraternal solidarity amid their shared isolation in an indifferent urban environment. As Lee Horsley observes (see 168), Eddie is confronting the noir dilemma that the past, in Goodis’s words, will not remain confined to “another city” (104) and that “the sum of everything was a circle [...] labeled Zero” (82). [→ page 40] Edward Webster Lynn was not always in retreat from the world, as the middle chapters of Down There reveal in a significant shift to extradiegetic discourse. Growing up in a dilapidated farmhouse set deep in the woods of southern New Jersey with a dysfunctional family, Edward became a child prodigy when his father taught him to play the piano. After receiving a scholarship to study at the Curtis Institute of Music, he at age nineteen gave his first concert in Philadelphia, coming to the attention of a respected manager based in New York City. On the day of signing a contract for his début recital, however, he was drafted into the U. S. Army and wounded three times in Burma during World War II. After convalescing, the ex-G.I. returned to New York, supporting himself by giving piano lessons to tenement-dwellers in the West Nineties, and fell in love with Teresa Fernandez. Three months later they were married. Not long thereafter tragedy struck when Teresa’s husband, then twenty-five and under contract to a manager named Arthur Woodling, gave four performances at Carnegie Hall, only to discover that Woodling had been sexually blackmailing Teresa. When in shame she leapt to her death from a fourth-story window, Goodis’s protagonist lapsed into “a time of no direction,” prowling the city’s five boroughs as a “wild man” intent on spilling blood wherever he encountered opposition by muggers and cops alike (82). That spree of violence ended when, after a reunion with his family at Thanksgiving, Edward recognized the nullity of their lives, including those of “two old hulks who didn’t know they were still in there pitching, the dull-eyed, shrugging mother and the easy-smiling, booze-guzzling father.” Adopting his parents’ escapist responses to the outside world—“the shrug,” “the smile,” “that nothing look” (87)—their youngest son, buffered from further human involvement, drifted from place to place before getting a job washing dishes and mopping the floor at Harriet’s Hut. One night, meekly asking permission from the bartender to try the establishment’s battered piano, Eddie was told, “All right, give it a try. But it better be music.” Shifting to the second-person pronoun, Goodis then writes in a pair of short paragraphs: “You lifted your hands. You lowered your [→ page 41] hands[,] and your fingers hit the keys. The sound came out[,] and it was music” (88).

If Eddie Lynn’s musical talent enables him to escape into oblivion among the Port Richmond mill workers, who readily accept him as one of their own, it also confers on him an identity that causes him to be misconstrued, leading later to lethal trouble. When early in Down There, for example, syndicate thugs attempt to seize his brother in Harriet’s Hut, Eddie enables Turley to get out a side door by toppling a stack of beer cases in their path, but his adroit timing brings him to the attention of the bar’s bouncer. A former professional wrestler known as the “Harleyville Hugger,” 43-year-old Wally Plyne knows a thing or two about what he calls a “tagteam play.” Realizing that he has given himself away, Eddie in another interpolation of internal dialogue “said to himself, Something is happening here[,] and you better check it before it goes further” (23). He manages to evade Plyne’s further questioning by reassuming the persona he knows the suspicious bouncer perceives him as being—namely, “the thirty-a-week musician,” a “nobody whose ambitions and goals aimed at exactly zero” (26). That dismissive estimation changes, however, with the introduction of Lena (no last name given) into the story.

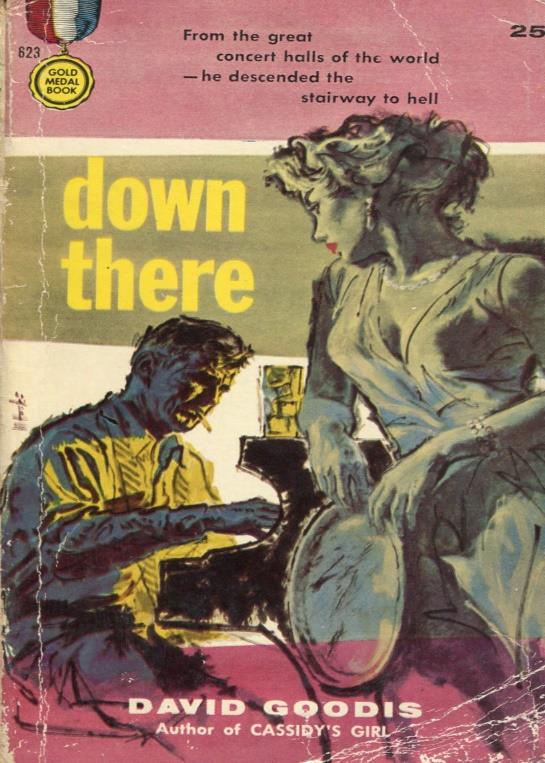

Like Goodis’s self-distancing protagonist, the bar’s waitress is “strictly solo” and marked by aloofness (13), a trait that puts her at a far remove from what Maysaa Husam Jaber describes as the author’s “criminal femmes fatales” in his other fiction (113-28). Lena brandishes a five-inch hatpin to ward off unwanted sexual advances by men, although that precaution has not deterred Harriet’s common-law husband, Wally Plyne, from fancying himself her protector. Repulsed by Plyne’s interest in her, Lena on the night of Turley’s escape, having glimpsed in him a quality belied by the piano player’s detachment, takes it upon herself to strike up a friendship. The book’s original cover reproduced below hints at her interest in Eddie. [→ page 42]

Although both studiously avoid betraying any sign of attraction, reciprocity is clearly at work. That bond strengthens a few days later when both are abducted by Feather and Morris, the syndicate’s foot soldiers, who are intent on tracking down Turley Lynn and his older brother Clifton for swindling the crime organization. While their captors are wending through traffic en route to the Delaware River Bridge, Lena engineers their escape before revealing that she has deduced his former identity as concert pianist Edward Webster Lynn. After chronicling Eddie’s past in Chapters 8-9, as already discussed, Goodis resumes his narrative in the present by recounting their trek on foot amid a gathering snowstorm back to Harriet’s Hut where Lena needs to collect wages she is owed. While supporting each other in traversing the slippery pavements, Eddie again succumbs to one of his self-admonitions conveyed in the form of an internal colloquy:

You better let go, damn it. Because it’s there again, it’s happening again. You’ll hafta stop it, that’s all. You can’t let it get you like this. [...]

Say, what’s the matter with your arms? Why can’t you let go of her? Now look, you’ll just hafta stop it.

I think the way to stop it is shrug it off. Or take it with your tongue in your cheek. Sure, that’s the system. At any rate it’s the system that works for you. It’s the automatic control board that keeps you way out there where nothing [→ page 43] matters, where it’s only you and the keyboard and nothing else. Because it’s gotta be that way. You gotta stay clear of anything serious. (89-90)

So resolved, Eddie finds his arms falling away from Lena while he adopts once more the “soft-easy smile” of nonchalance and detachment (90), but the seed of emotional involvement has been sown, leading to a chain of circumstances that he can neither foresee nor avoid.

The scenario as Goodis constructs it suggests a Sartrean crisis in which the fatality of choice is bearing down on his protagonist. 3) The process begins when Lena and Eddie are collecting their week’s salaries. When Wally feigns ignorance about how Feather and Morris discovered Eddie’s address in order to abduct him, Lena fearlessly exposes the bouncer’s betrayal. As she continues to taunt Plyne for his duplicity, Lynn tries to convince himself that “nothing matters” and is eager to “sit down at the keyboard, to start making music. That’ll do it, he thought, That’ll drown out the buzzing” (98). This time, however, Eddie’s usual recourse for escape fails him. As Wally closes in on Lena to strike her several times in the face, the mild-mannered piano player intervenes by abandoning his usual stance of non-involvement. When Eddie’s initial overtures to “Leave her alone” go unheeded (103), he drops into a fighting stance and parries his opponent’s blows while urging him to desist. Humiliated by his punishment in front of the bar’s local clientele, Plyne seizes the broken leg of a chair and, swinging it as a cudgel, forces Eddie to retreat. As the distance between them lessens, the smaller man vaults over a counter, grabs a sharp bread knife, and bluffingly forces Wally to flee into the rear alley. Cornered in a back yard, the former wrestler sees Eddie toss the knife aside into a snow drift but, unable to forget his humiliation in the bar, another sign of its clientele’s desperate need for a communal identity, lunges forward to hoist the piano player in a suffocating bear hug. About to pass out, Eddie recovers the knife and, intending only to wound Plyne in the arm, kills him when Wally shifts position. A court of law would likely rule the death a case of justifiable self-defense, but Goodis relies once more on internal dialogue to expose Eddie’s predicament: [→ page 44]

You say accident. What’ll they say? They’ll say homicide.

They’ll add it up and back it up with their own playback of what happened in the Hut. The way you jugged at him with the knife. The way you went after him when he took off. But hold it there, you know you were bluffing.

Sure, friend. You know. But they don’t know. And that’s just about the size of it, that bluffing business is the canoe without a paddle. (113)

This debacle, however, is only the prelude to what ensues as the unforeseeable consequences of his intervention on Lena’s behalf, reinforcing the existentialist premise of the fatality of choice.

Leonard Cassuto maintains that the undercurrent of “anxious foreboding in Goodis’s writing” (102), especially pronounced in his third novel Nightfall (1947), signifies what O’Brien terms a “sense of the world as an abyss made for falling into” (94), all the more proximate for those confined by economic forces to America’s inner cities after World War II. Such doomed inevitability plays itself out in the final third of Down There. After finding an exhausted Eddie in the back alley and sequestering him in the cellar of Harriet’s Hut, Lena returns six hours later with a car she commandeers from her landlady. Avoiding the police, they make their way across the Delaware River Bridge to South Jersey, Eddie thinking all the while that “we’re seeing a certain pattern taking shape. It’s sort of in the form of a circle. Like when you take off and move in a certain direction to get you far away, but somehow you’re pulled around on that circle, it takes you back to where you started” (128). Like Albert Camus in Le Mythe de Sisyphe (1942), Goodis emphasizes the circularity of ontological entrapment. Thus it is that, after Lena drops him off at the Lynns’ farmhouse, now a hideout for his brothers who have sent their parents away, Eddie tries to establish some rapport, his thoughts all the while “centered on the waitress” and her safe return to Philadelphia (137). When Lena arrives the next day to tell Eddie that all charges against him have been dropped because she persuaded the Hut’s owner and patrons, in a telling example of communal solidarity, to avow that Wally’s death was an accident, Feather and Morris also reappear, having followed her to the farmhouse. In the ensuing gun battle Lena is killed, while Clifton and Turley Lynn manage to escape. Taking her body to a neighboring town, Eddie is grilled [→ page 45] for thirty-two hours about the victim’s identity: “He repeated what he’d told them previously, that she was a waitress and her first name was Lena and he didn’t know her last name” (156). So ends Down There, but not before Eddie is seated once more at the piano in Harriet’s Hut. Feeling that he has nothing left in him to give, Goodis’s protagonist nonetheless takes up his usual position.

His eyes were closed. A whisper came from somewhere, saying, You can try. The least you can do is try.

Then he heard the sound. It was warm and sweet and it came from a piano. That’s fine piano, he thought. Who’s playing that?

He opened his eyes. He saw his fingers caressing the keyboard. (158)

No words are wasted in this short and stark novel, attesting to its vernacular inscription, rendered in intradiegetic passages, of life on the outer edges of an upwardly mobile mainstream society in 1950s America. In a biographical profile of the author, James Sallis contends that “David Goodis rewrote essentially the same book again and again, ceremonially encoding his own fall from promising writer [with the publication of Dark Passage in 1946] to recluse” (7). Goodis’s pulp novels set in Philadelphia, he alleges, constitute a “threnody [...] about losers, outcasts, and derelicts, the unchosen, the discarded” (48). Haut proposes that such identification “indicates a class-based separation between writers who have the status of literary artists and those who have been relegated to the status of literary workers” (3), but this extrapolation tends to delimit Goodis’s significance in mid-twentieth-century literature. However narrow his sociological frameworks, Goodis’s fiction recurrently addresses issues that lie at the core of America’s experiment in egalitarian democracy.

Carrollton, GA

Works Cited

Cassuto, Leonard. Hard-Boiled Sentimentality: The Secret History of American Crime Stories. New York: Columbia UP, 2009.

Dylan, Bob. “Love Minus Zero/No Limit.” Bringing It All Back Home. Columbia Records, 1965.

Gertzman, Jay A. Pulp According to David Goodis. Tampa, FL: Down & Out, 2018. Godwin, Richard. Foreword. Pulp According to David Goodis. Jay A. Gertzman, Tampa, FL: Down & Out, 2018. 1-4.

Goodis, David. Shoot the Piano Player. New York: Vintage Crime/Black Lizard, 1990. Rpt. of Down There. 1959. [Retitled after François Truffaut’s 1960 film adaptation.]

Haut, Woody. Pulp Culture: Hardboiled Fiction and the Cold War. London: Serpent’s Tail, 1995.

Horsley, Lee. The Noir Thriller. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001.

Jaber, Maysaa Husam. Criminal Femmes Fatales in American Hardboiled Crime Fiction. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

O’Brien, Geoffrey. Hardboiled America: Lurid Paperbacks and the Masters of Noir. 1981. Expanded ed. Boston: Da Capo, 1997.

Rich, Nathaniel. “So Deep in the Dark.” Rev. of Five Noir Novels of the 1940s and 50s, by David Goodis, ed. Robert Polito. New York Review of Books 21 June 2012: 38-39. Sallis, James. Difficult Lives: Jim Thompson, David Goodis, Chester Himes. New York: Gryphon Books, 1993.

Schmid, David. “David Goodis.” American Hard-Boiled Crime Writers. Vol. 226 of Dictionary of Literary Biography. Detroit: Gale, 2000. 157-65.

Schmid, David. “A Different Shade of Noir: Masculinity in the Novels of David Goodis.” Paradoxa: Studies in World Literary Genres. 16 (2001): 153-76.

Snyder, Robert Lance. “David Goodis’s Noir Fiction: The American Dream’s Paralysis.” European Journal of American Studies 16.1 (2021): n.pag.<https://doi.org/10.4000/ejas.16718> 15 Sept. 2021.